Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 37,2004

106

THE SURFACE CIRCULATION IN THE EASTERN BASIN OF THE MEDITERRANEAN SEA

N. Hamad, C.Millot* and I. Taupier-Letage

Antenne LOB-COM-CNRS, BP 330, F-83507 La Seyne-sur-Mer, France - * cmillot@ifremer.fr

Abstract

The Atlantic Water (AW) circulation schemata widely referred to nowadays (1, 2, 3) represent a cross-basin meandering jet, thus

disagreeing with a pioneering work (4) and a former analysis of IR images (5, 6). A roughly similar controversy was elucidated in the

western basin where this imagery was proven reliable. This has motivated the visual analysis of daily/weekly (~1000, 1996-2000) and

monthly (since 1985) composites. In our schema, the mean ?ow is anticlockwise along the upper part of the continental slope and it

generates mesoscale eddies that tend to follow the deeper isobaths. Other eddies are induced by the Etesians every year. All eddies can

have several-year lifetimes, propagate and merge.

Key-words: Mediterranean Sea, eastern basin, IR imagery, surface circulation, mesoscale eddies

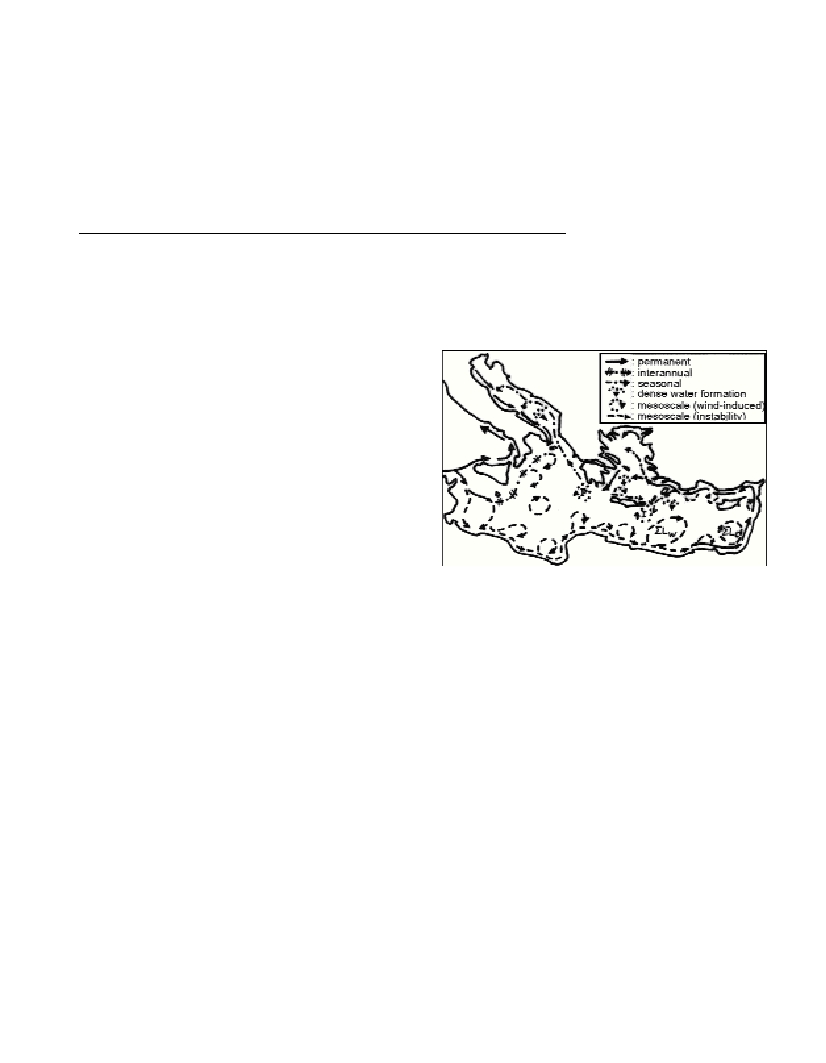

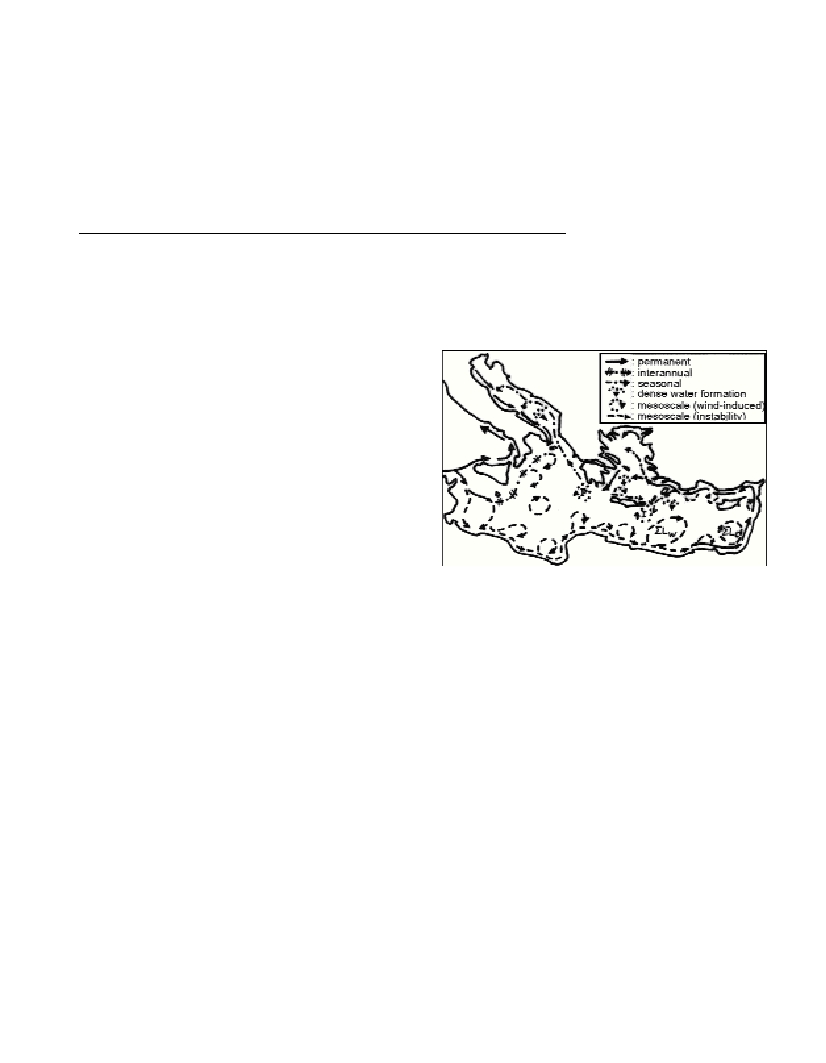

Overall, the AW circulation (100-200 m thick) is alongslope and

anticlockwise. It is permanent from Tunisia to Turkey and seasonally

variable in the Aegean, the Ionian around Greece and the Adriatic. A

branch, having spread for years (up to early 1998) from the Sicily

channel towards the northern Ionian before vanishing, represents

interannual (not seasonal) variability. Mesoscale eddies, generated by

the instability of the AW ?ow or by orographic effects on the Etesians,

were not correctly described before. Although they have

characteristics almost specific to each subbasin and/or to their

generation mechanism, the largest are anticyclonic, reach diameters of

a few 100s km and can be tracked for months/years propagating at up

to a few km/d . They represent a relatively large amount of AW and

play a fundamental role in spreading it seaward.

In the southern Ionian, large eddies generated by the AW ?ow as

soon as the depth exceeds a few 100s m seemingly drift along

intermediate to deeper isobaths, probably depending on their vertical

extent. An eddy, initially found east of Sicily, drifted southwards as far

as Libya where it disturbed the AW alongslope ?ow more than two

years later. All eddies originated either in the north (including Pelops)

or in the south can drift in the central Ionian and create there a

complex eddy-field that, being only partially investigated, was

incorrectly associated with the alleged “Atlantic Ionian Stream” and

“Mid-Ionian Jet”. On average, AW does not cross the Ionian in its

central and/or northern parts but ultimately concentrates in the south

as an alongslope anticlockwise ?ow that is unstable and generates

anticyclonic (Libyan) eddies.

These eddies then propagate downstream along the eastern Libyan

slope and eventually interact with Ierapetra, thus increasing the

interannual variability of the latter. In addition, Ierapetra can remain

stationary more than one year and thus be intensified the year after, it

can drift over 100s km, merge with a former Ierapetra and / or reach

the Libyan and Egyptian slopes; hence, successive Ierapetra’s can be

found simultaneously. At the entrance of the Levantine, the largest

Libyan eddies tend to follow the deeper isobaths and thus detach from

their parent current. Then, together with Ierapetra, they generally

remain trapped by the Herodotus trough before finally decaying.

Contrary to what has been believed hitherto, the “Mersa-Matruh” area

(named

S

L

W

) is occupied not by a recurrent / permanent feature but

by slowly propagating and merging anticyclonic eddies originated

elsewhere. The northwestern edges of such mesoscale eddies must

have been confused with a northeastward “Mid-Mediterranean-Jet”.

The specificity of that area is thus due to processes never foreseen

before.

The Shikmona area (named

S

L

E

) is occupied by an offshore

anticyclonic structure fed by various kinds of small-scale eddies

originated alongslope. Both the “Cilician Current” and the “Asia

Minor Current” are the continuity of the overall alongslope ?ow that

meanders and generates medium-size eddies. The ?ow continues

either into the Aegean, especially in winter, or southwestwards, up to

feeding Ierapetra. North of Crete, most eddies propagate eastwards. In

the northern Ionian, the ?ow towards the Adriatic displays a marked

seasonal variability, intensifying in winter. In the Adriatic, it clearly

surrounds the dense water formation zone in winter.

The monthly-composite analysis confirms that an alongslope and

anticlockwise schema also applies to the late eighties - early nineties

at least. In addition, all features evidenced with all available in situ

data sets (in particular the POEM ones) can be seen with the IR

imagery. It is thus concluded that i) all available data sets are reliable

and ii) the POEM schemata (1, 2, 3) result from a misinterpretation of

the observed features. Although mainly descriptive, our visual

analysis of IR images allows proposing an alternative realistic schema

of the AW circulation. The mean ?ow is anticlockwise alongslope and

unstable. Mesoscale (100-200 km) anticyclonic eddies, propagate for

months/years at up to a few km/d and tend to follow the deeper

isobaths. An extended version of this paper is presently submitted to

Progress in Oceanography.

References

1-Robinson A.R., Golnaraghi M., Leslie W.G., Artegiani A., Hecht A.,

Lazzoni E., Michelato A., Sansone E., Theocharis A., and Ünlüata Ü.,

1991. The Eastern Mediterranean general circulation : features, structure

and variability. Dyn. Atm. Oceans, 15: 215-240.

2-Robinson A.R., and Golnaraghi M., 1993. Circulation and dynamics of

the Eastern Mediterranean Sea; Quasi-Synoptic data-driven simulations.

Deep Sea Res., 40: 1207-1246.

3-Malanotte-Rizzoli P., Manca B.B., Ribera d’Alcala M., Theocharis A.,

Bergamasco A., Bregant D., Budillon G., Civitarese G., Georgopoulos D.,

Michelato A., Sansone E., Scarazzato P., and Souvermezoglou E., 1997. A

synthesis of the Ionian Sea hydrography, circulation and water mass

pathways during POEM-Phase I. Prog. Oceanogr.,39:153 -204.

4-Nielsen J.N., 1912. Hydrography of the Mediterranean and adjacent

waters. Rep. Dan. Oceanogr. Exp. Medit., 1: 77-192.

5-Le Vourch J., Millot C., Castagné N., Le Borgne P., and Olry J.P., 1992.

Atlas of thermal fronts of the Mediterranean Sea derived from satellite

imagery. Mém. Inst. Océanogr. Monaco, 16.

6-Millot C., 1992. Are there major differences between the largest

Mediterranean Seas? Bull. Inst. Oceanogr. Monaco, 11: 3-25.