Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 37,2004

127

CORRECTION OF MODELED SEA SURFACE WIND IN ORDER TO IMPROVE WAVE FORECAST

A. Murashkovsky*, I. Gertman

Israel Oceanographical and Limnologial Research, National Institute of Oceanography, Haifa 31080, Israel - * amur@ocean,org.il

Abstract

A method for correcting wind input to WAM model is proposed in order to re?ect wind gusts, otherwise not present in the atmospheric

models output. The method is based on wind field vorticity analysis and does not require any external data. The wave forecast resulting

from winds corrected by this method was compared to real data, as well as to forecasts resulting from a different correction technique.

Keywords: wind gusts, WAM model

Introduction

Operational wave forecasting system based on WAM model for the

Eastern Mediterranean was implemented in IOLR since fall 1997 [1].

The results of the wave forecast and hindcast produced by the system

were compared to true data from Hadera GLOSS station from the

beginning of the project.

From the very beginning the comparisons showed that H

s

is

underestimated and this fault increased with H

s

increases. The

problem of the wave model underestimating H

s

isn’t new, it was

addressed before, e.g. Cavalieri [2], and it is attributed to negative

errors in closed basins. However, it was suggested that during severe

storms another factor may in?uence the H

s

growth, namely wind

gusts, which, typically, are not represented in the output of

meteorological models.

Several methods have been suggested for the introduction of wind

gustiness into wave model input. Abdalla and Cavalieri [3] used

fluctuations represented by Gaussian process, characterized by

coherence in time. Another method proposed adding a constant factor

to the wind field. Wave Watch III, as of ver. 1.18 [4] used term

dependent on T

air

-T

w

difference to represent atmospheric instability

and calculate an effective wind speed.

This paper proposes a new method, based on the assumption that

most severe wind gusts occur during the passage of atmospheric

fronts, and are indicated by significant changes in the wind direction.

Methods and materials

Hess [5] defines an atmospheric front as zone of rapid transition

from one temperature to another. It also noted that significant wind

direction changes occur in frontal zones. The frontal zones are

characterized by strong atmospheric instabilities, often resulting in

severe weather, and are usually accompanied by strong wind gusts.

The quantitative characteristic of vector field direction change is its

curl, which leaded to defining “gustiness” of the wind field as

The actual correction was calculated using measured data at Hadera

GLOSS station, and resulted in

Results and discussion

Two sources of wind input were used during the verification of the

method: the SKIRON forecasting system from University of Athens

(output every 6 hours, 0.2x0.2º resolution); and the Bracknell model

by UKMO (output every 6 hours, 0.833x0.566º resolution). Both T

air

-

T

w

and wind vorticity correction techniques were applied and the

results were compared to the measured data. The immediate result of

the comparisons revealed that the impact of both methods on low

resolution wind was insignificant, so that only SKIRON wind was

utilized subsequently.

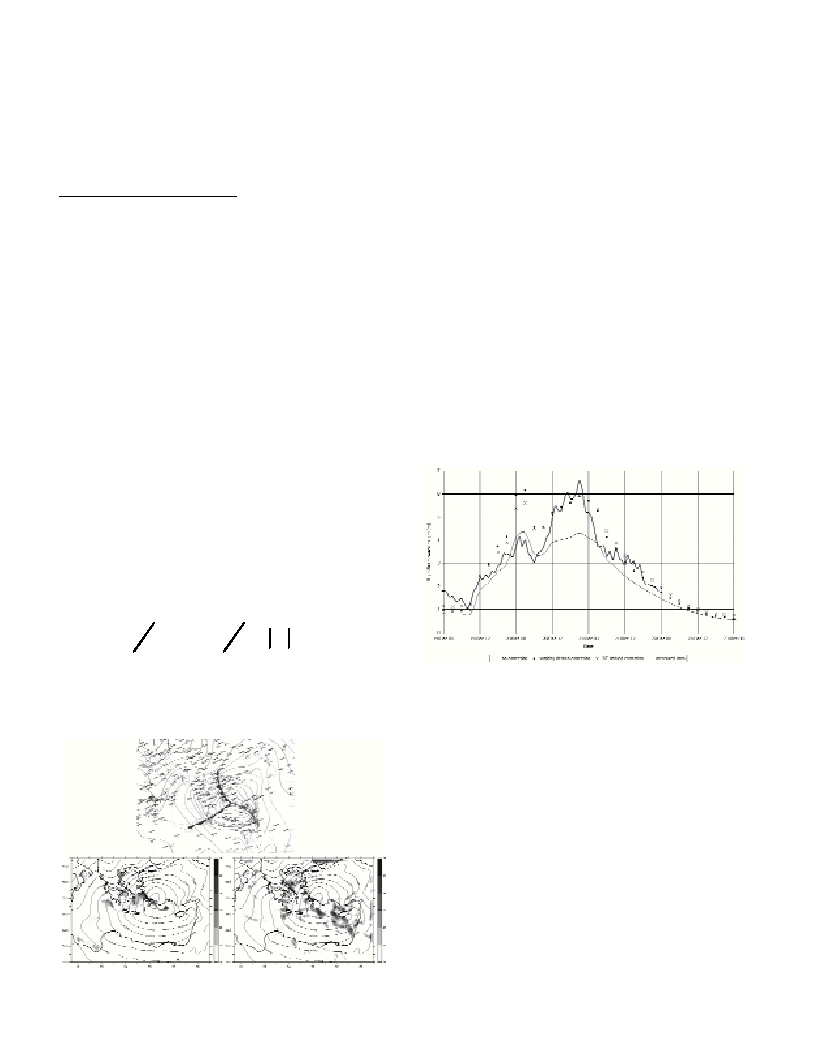

On the synoptic map three frontal zones are clearly visible: a hot

one and two cold ones. Predictably dT derived correction is very small

in the hot frontal zone, while the vorticity derived correction produces

significant values. The correction based on vorticity also increased

near the shores, where wind changes its direction.

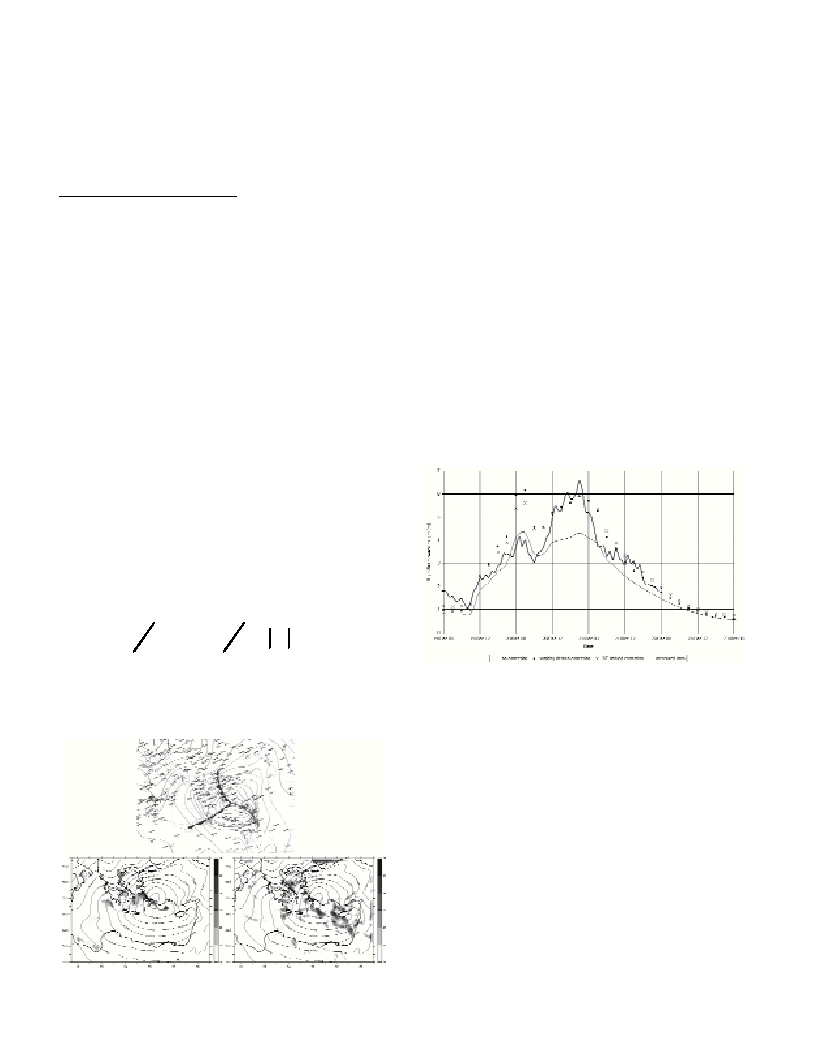

Another comparison was carried out by using the WAM model for

the Levantine basin to produce wave hindcast with wind input

corrected by various methods. The results were compared to data

measured at Hadera GLOSS station. It is clear that both methods

improve the forecasts significantly, when compared to forecasts

produced with uncorrected wind input. The preliminary studies

confirm that both methods produce similar results, while vorticity

derived technique requires less data.

Fig. 2. Comparison of significant wave height with wind input produced

by different methods.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank sincerely to Prof. G. Kallos from SKIRON group

for providing us with wind data for this work.

References

1-Gertman I. Rosen D.S., Sandler K. and Raskin L., 2000. Comparison

of two years of wind and wave hindcast via WAM based operational

forecasting system versus field and other models data. Proceedings of 6th

international workshop on wave hindcast and forecast. pp 91-98.

2-Cavalieri L., 1994. Orographic Effects, pp. 293-294. In:Komen G.J

(ed) Dynamics and Modeling of Ocean Waves. Cambrige Univ. Press,

New York.

3-Abdalla S. and Cavalieri L., 2002. Effect of wind variability and

variable air density on wave modeling. Journal of geophysical research,

107: 17-1 – 17-17.

4-Tolman H. L. 1999a. User Manual and system documentation of

Wavewatch-III, ver 1.18. OMB Contribution No 166.

5-Hess S. L., 1959. Introduction to theoretical meteorology. Holt,

Rinehart and Winston, New York.

65

.

0

)

(

*

399

.

0

+

=

G

Ln

G

corr

10

10

10

)

(

)

(

U

U

U

U

U

G

Y

X

r

r

r

r

r

·

?

?

?

?

?

?

?

×

?

?

+

?

×

?

?

=

Fig. 1. Frontal zone wind correction, calculated by different methods

during severe storm. Top : synoptic map; bottom left : dT derived

correction; bottom right : vorcity derived correction.