AFRICAN DUST DEPOSITION AND OCEAN COLOUR IN THE EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

François Dulac*, Cyril Moulin, Hélène Planquette, Michael Schulz, Michael Tartar

Laboratoire des Sciences du Climat et de l’Environnement - CEA-Saclay 709, F-91191 Gif-Sur-Yvette Cedex, France - *fdulac@cea.fr

Abstract

We study the impact of Saharan dust deposition on chlorophyll concentrations in the Mediterranean using ocean colour products and

simulated dust deposition ?uxes. Chlorophyll increases follow most dust deposition events but dust fertilization and wind-related effects

cannot be disentangled.

Keywords: Surface water fertilization, Dust deposition, Chlorophyll, SeaWiFS, LMDz-INCA.

Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 37,2004

190

Introduction

African dust deposition significantly contributes to soluble

phosphorus inputs to Mediterranean surface waters (1), where it is the

limiting nutrient, and probably sustains the marine productivity(2

)

.

This work aims at investigating this possible fertilization of low

productive Mediterranean waters.

Data and method

SeaWiFS daily level-3 maps (~9x9km

2

) of chlorophyll

concentration ([Chl]) were obtained from NASA(3) for 1998 2000.

Only part of the basin is observed every day because of clouds and

orbital characteristics.

The atmospheric dust cycle was simulated at a resolution of

1.84°x2.25°with LMDz-INCA, a 3-D AGCM coupled with

chemistry and aerosols (4). We extracted daily integrated dry and wet

dust deposition ?uxes (F=F

d

+F

w

).

We averaged [Chl] within the model grid (~600 pixels/cell) and

selected four grid cells across eastern Mediterranean: Southern

Central (SC: 18°E, 33.06°N), Eastern Central (EC: 22.5°E, 34.90°N),

South-western Levantine (SL: 24.75°E, 33.06°N), and Northern

Levantine (NL: 29.25°E, 34.90°N). We rejected days with

=

25% of

pixels per grid cell. This left 50-60% of days and we filled gaps using

a 7-day moving average.

Results and discussion

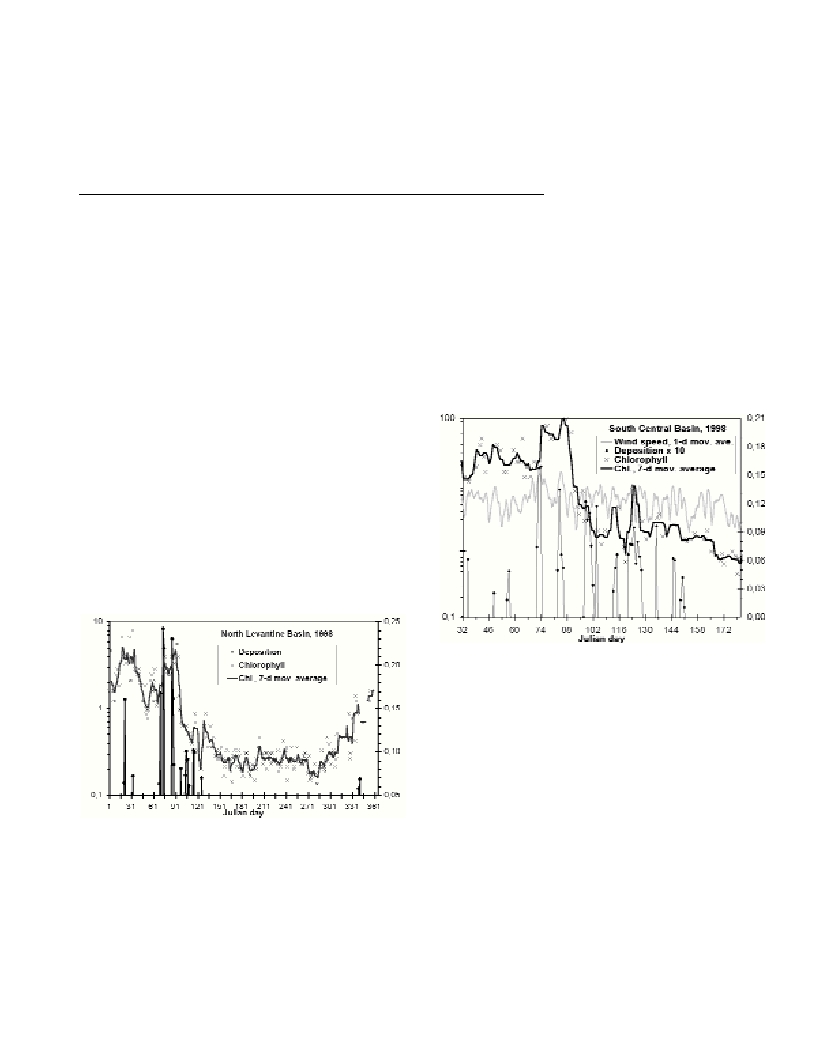

Maximum (resp. minimum) surface [Chl] at a given site varies

between 0.20 and 0.34 (0.04 and 0.06) mgm

3

. The seasonal cycle

shows a winter maximum of 0.20±0.05 mgm

3

in January-February,

with another, occasionally absolute, maximum in March (Fig. 1).

[Chl] drops down in spring and remains low (0.05-0.10 mgm

3

) from

May to September. From October, [Chl] slowly increases to its winter

maximum.

Fig. 1. Daily dust deposition, daily and 7d averaged chlorophyll at NL in

1998.

A dust outbreak generally causes high deposition at most sites.

Overall range in F is 8.938.7 gm

2

yr

1

, with a factor 2-3 of

interannual variability at a given site, and no clear trend from one year

or one site to the other. The fallout is controlled by a few wet

deposition events (F

w

/F>93%). Maximum F

w

of 15.7 gm

2

yr

1

is

simulated at SC and F

w

>1gm

2

d is reached up to 9dyr

1

. F

d

exceeds 0.1 gm

2

yr

1

for only 910 dyr

1

, with a maximum of 1.24g

m

2

yr

1

at SL. Most of highest deposition events and annual

deposition occur during March-May. Summer fallout never exceeds

0.25 gm

2

d

1

. The simulated seasonal cycle is consistent with

observations (5,6).

Laboratory experiments support an increase of 8 mgChlm

2

(or

0.08 mgChlm

3

in a surface mixed layer of 100m) per gm

2

of dust

deposition (7)with a lag time of ~48 hours (8). For a summer dust

deposition of 0.1 gm

2

in a mixed layer of 20m, the expected

increase is 0.04 mgChlm

3

. Our data set shows in accordance

0.020.16 mgm

3

increases in [Chl] shortly following dust fallout, and

thus supports a dust fertilization of Mediterranean waters.

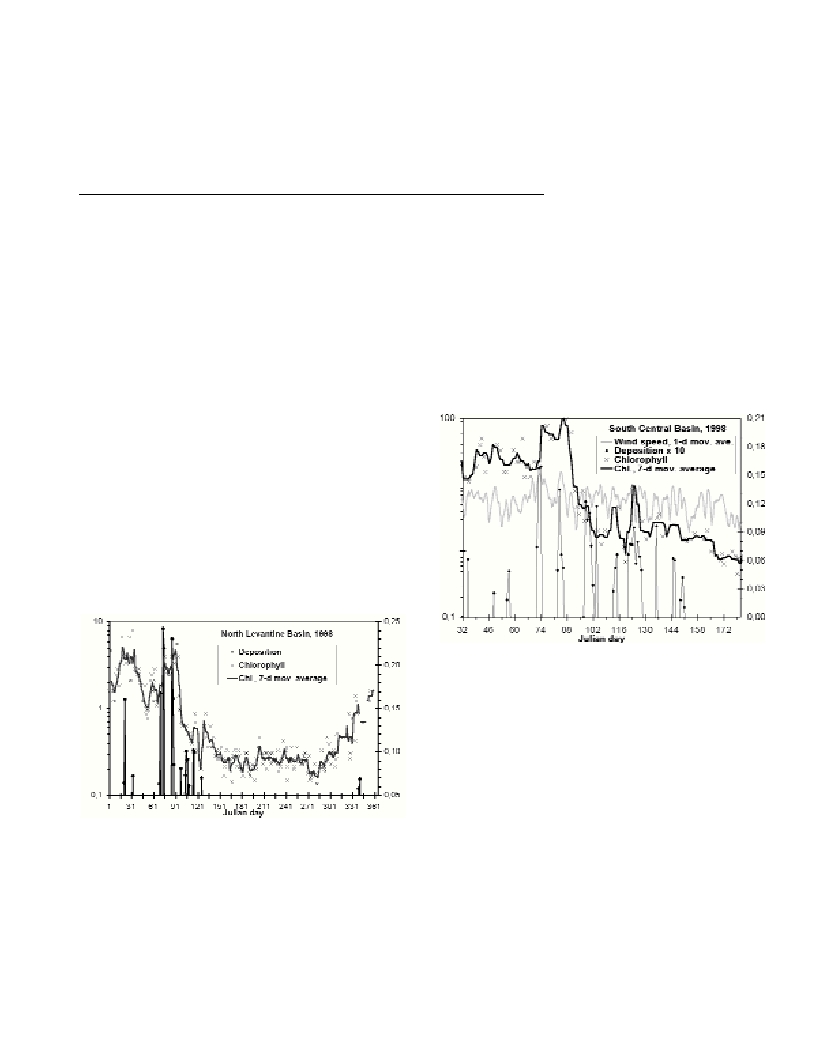

However, we also find a good correspondence between high surface

winds and [Chl] peaks, and dust events are generally associated with

wind peaks (Fig.2). Surface wind controls the mixing between

surface waters and deeper ones, richer in nutrients. Observed [Chl]

increases can thus be contributed by both dust deposition and wind.

Coupled biogeochemical-circulation model and appropriate in situ

measurements are necessary to unravel both effects.

Fig. 2. Daily dust deposition, daily and 7d averaged chlorophyll, and

wind speed at SC, between February 1 and June 30, 1998.

Acknowledgement.This work was supported by the French Space

Agency (CNES).

References

1-Bergametti G., et al., 1992. Source, transport and deposition of

atmospheric phosphorus over the northwestern Mediterranean. J. Atmos.

Chem., 14: 501-513.

2-Ridame C., and Guieu C., 2002. Saharan input of phosphate to the

oligotrophic water of the open western Mediterranean Sea. Limnol.

Oceanog., 47: 856-869.

3-http://seawifs.gsfc.nasa.gov/SEAWIFS.html

4-Bauer S.E., et al.,in press. Global modelling of heterogeneous

chemistry on mineral aerosol surfaces: The in?uence on tropospheric

ozone chemistry and comparison to observations. J. Geophys. Res.

5-Nihlén T., et al.,1995. Monitoring Saharan dust fallout on Crete and its

contribution to soil formation. Tellus, 47B: 365-374.

6-Kubilay N., et al.,2000. An illustration of the transport and deposition

of mineral dust onto the eastern Mediterranean. Atmos. Environ., 34: 1293-

1303.

7-Ridame C., and Guieu C., 2002. Saharan input of phosphate to the

oligotrophic water of the open western Mediterranean Sea. Limnol.

Oceanog., 47: 856-869.

8-Ridame C., 2001. Rôle des apports atmosphériques d’origine

continentale dans la biogéochimie marine: Impact des apports sahariens

sur la production primaire en Méditerranée. PhD diss., Univ. Paris-6.