Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 37,2004

276

HOW MUCH DO BACTERIA DEPEND ON PHYTOPLANKTON METABOLISM?

González-Benítez N.

1*

, Gattuso J.P.

2

1

Área de Biodiversidad y Conservación. ESCET. Universidad Rey Juan Carlos. E-28933 Madrid, Spain

2

LOV - UMR 7093. BP 28. F-06234 Villefranche-sur-Mer, France

Abstract

The degree of coupling between phytoplankton and bacteria was estimated in the Bay of Palma during summer 2002 by comparing the

relative proportions of particulate and dissolved primary production with bacterial carbon demand. On the whole, these results suggest,

that the bacterial growth efficiency responds to changes in phytoplankton production, increasing as the primary production increases. In

summary, there is lack of dependence of bacterial metabolism on algal production in the oligotrophic area, whereas the most productive

area showed a strong coupling between phytoplankton and bacterioplankton.

Keywords: Bacterial metabolism, PER, oligotrophy, BGE

Introduction

The production of dissolved organic carbon (DOC) is important in

oceanic biogeochemistry and there are many different mechanisms of

production although the ultimate source is phytoplankton. Dissolved

primary production (DOC-pr) in marine systems has been often

ignored because it is considered to be very low compared with the

particulate fraction (POC-pr). Some authors (1) have suggested that

the rate of POC-pr and the relative contribution of DOC-pr to total

carbon fixation (PER) are inversely correlated, although other

authors(2) have reported that PER is constant across marine and

freshwater systems. Thus the issue, still unresolved, is important,

since dissolved organic carbon represents an important source of

labile carbon for heterotrophic bacteria(3). Depending on the bacteria

growth efficiency (BGE), DOC consumed by bacteria will be either

converted to POC or respired as CO

2

decreasing the organic carbon

transfer to higher trophic levels. Both processes of bacterial

metabolism, production and respiration, against the general idea are

not well coupled, providing a metabolic ?exibility necessary for

survival under oligotrophic conditions(4). According to a recent

study(5) the carbon cycle is mainly determined by the combined

activities of bacteria and phytoplankton. Therefore, variations in BGE

will affect the degree of coupling between bacteria and phytoplankton

and, consequently, the biogeochemical cycles within marine

ecosystems. Given the lack of simultaneous measurements of the

BGE and the balance between DOC-pr and POC-pr, particularly in

oligotrophic regions (although they cover ca 70% of the total marine

surface), we have carried out the present experiment.

Material and methods

The study was conducted at Bay of Palm during June 2002. The

water samples were collected at four depths between surface and 15

or 30 m depth. For phytoplanktonic POC-pr and DOC-pr rates, the

seawater samples were dispensed into 30 ml glass bottles (three clear

and one dark), spiked with 740 Kbq (20

µ

Ci) NaH

14

CO

3

and

incubated in situduring the daylight period (12 h). Bacterial

production (BP) was estimated as the rate of radioactive Leucine

incorporation(6). For bacterial respiration (BR), the seawater samples

were filtered, using a gentle filtration system (0.8 µm). The filtered

water was incubated in 60 ml borosilicate glass bottles at in situ

temperature (

±

1 şC) in the dark over 12, 24 and 48 h.

Results

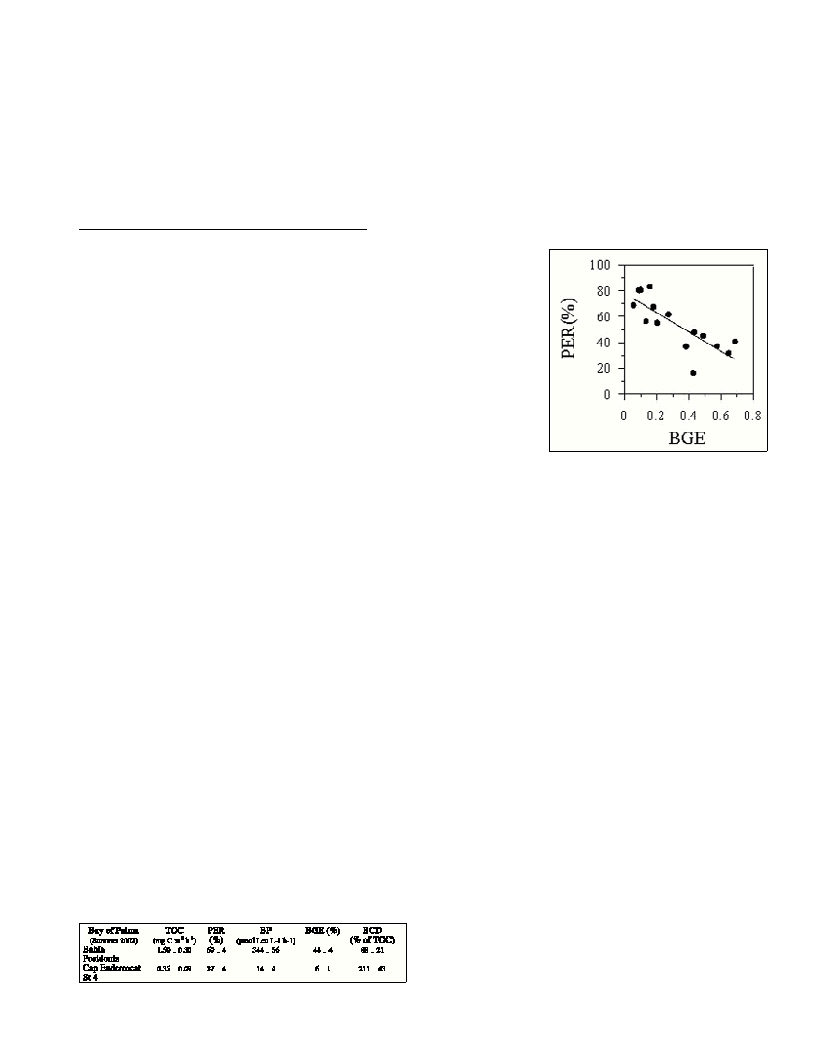

We observed two contrasting regions within an oligotrophic aquatic

system (Table 1). The percent of extracellular release (PER) was

significantly lower within the most productive areas. However,

bacterial production (BP) and BGE were higher in the most

productive areas. BGE increased as the relative contribution of DOC-

pr to total carbon fixation decreased (Fig. 1).

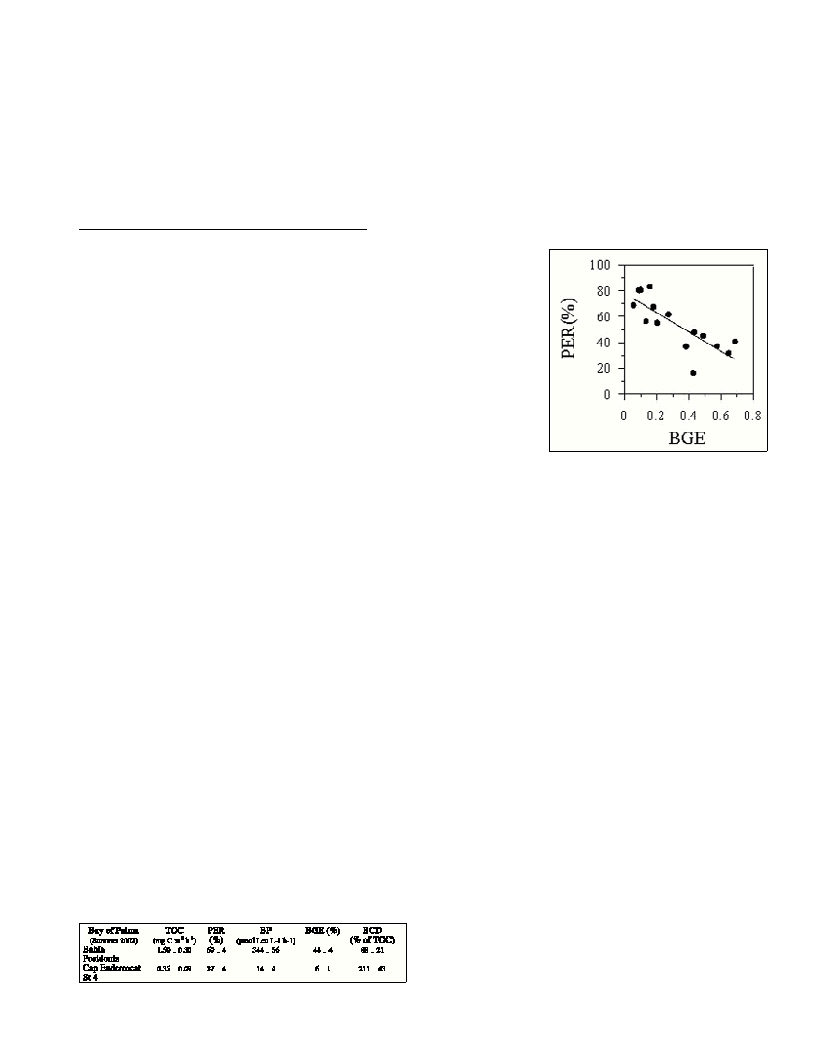

Table 1.-Mean (±SE) values of total carbon fixation (TOC-pr), percent of

extracellular release (PER), bacterial production (BP), bacterial growth

efficiency (BGE) and bacterial carbon demand (BCD) during summer

2002 in the Bay of Palma.

Conclusions

The relative con-

tribution of DOC-pr

to total primary

production decrea-

ses as the produc-

tivity of the system

increases. In agree-

ment with a recent

study(7), this result

provides evidence

that PER is not

constant, even wi-

thin oligotrophic

waters.

There was an im-

portant bacterial

response to the variability in primary production by adapting their

metabolism to this oligotrophic environment. BGE responded to

changes in phytoplankton production, increasing as the primary

production increased.

The organic carbon was consumed by bacteria less efficiently

within the most oligotrophic area and most of the carbon was respired.

Whereas the area with higher primary production, the energetic cost

of bacterial growth appeared to decrease and therefore BGE

increased.

There was a clear evidence of the small scale spatial variability

within this oligotrophic aquatic system showing lack of dependence

of bacterial metabolism on algal production within the less productive

area, and strong coupling between phytoplankton and

bacterioplankton within the most productive area.

References

1-Fogg G.E., 1983. The ecological significance of extracellular products

of phytoplankton photosynthesis. Bot Mar.,26: 3-14.

2-Baines S.B., Pace M.L., 1991. The production of dissolved organic

matter by phytoplankton and its importance to bacteria: patterns across

marine and freshwater systems. Limnol Oceanogr.,36:1078-1090.

3-Kirchman D.L., Suzuki Y., Garside C., Ducklow H.W., 1991. High

turnover rates of dissolved organic carbon during a spring phytoplankton

bloom. Nature, 352: 612-614.

4-del Giorgio P.A., Cole J.J., 1998. Bacterial growth efficiency in natural

aquatic systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst.,29: 503-541.

5-Azam F., 1998. Science, 280:694-696.

6-Smith D.C., Azam F., 1992. A simple economical method for

measuring bacterial protein synthesis rates in seawater using

3

H-Leucine.

Mar. Microb. Food Webs,6: 107-114.

7-Moran X.A.G., Estrada M., Gasol J.M., Pedrós-Alió C., 2002.

Dissolved primary production and strength of phytoplank-

ton–bacterioplankton coupling in contrasting marine regions. Microb

Ecol.,44: 217-223.