Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 37,2004

289

BACTERIAL BIOMASS IN SEDIMENTS OF COASTAL ADRIATIC SEA

S. Šestanovic*, M. Šolic and N. Krstulovic

Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Split, Croatia - * sesta@izor.hr

Abstract

The changes in bacterial biomass and morphological diversity of bacterial cells were studied in sediments of the eastern middle Adriatic

Sea. Bacterial biomass showed seasonal changes, varying from 78 to 378 mg C g

-1

. Rods dominated bacterial biomass during the whole

year. The majority of cocci biomass consisted of cells with the volume between 0.01 -0.5 mm

3

. During January and December, filamentous

bacteria covered up to 17% bacterial biomass.

Key words: bacterial biomass, sediment, Adriatic Sea

Introduction

Sediment bacteria comprise a large fraction of total benthic

biomass. To elucidate their trophic role, accurate measurements of

their biomass are needed. The changes in bacterial biomass depend

upon environmental conditions. Nutrient limitations can lead to the

formations of ultramicrocells (1). Under heavy protozoan grazing, the

distribution of bacterial cell types may shift toward filamentous forms

resistant to grazing (2).

Materials and methods

Undisturbed sediment cores were collected monthly, from January

to December 2002, with a piston corer, at one coastal station in

Kaštela Bay, middle Adriatic Sea. Bacteria were counted and sized

under epi?uorescent microscope (3). The volume of each cell was

calculated following equation of (4). Cell volumes were converted to

bacterial biomass using the equation given by (5). The results were

expressed in grams of sediment dry weight.

Results

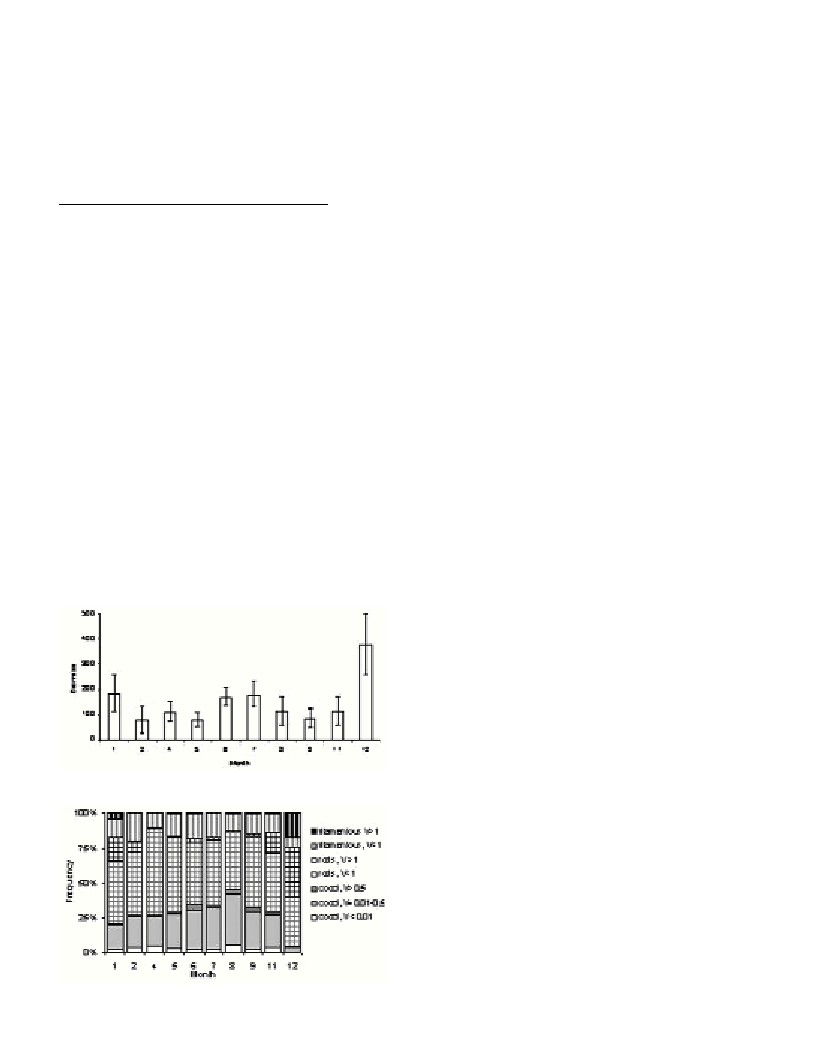

Bacterial biomass ranged from 78 to 378

µ

g C g

-1

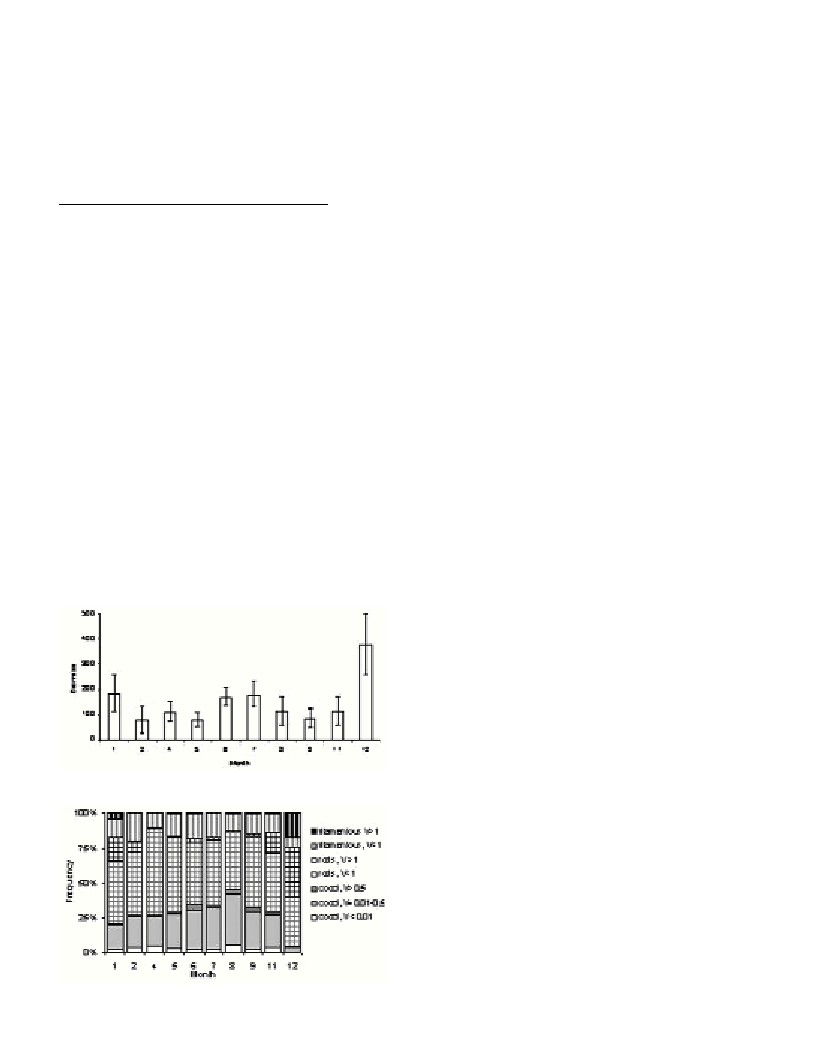

(Fig. 1). Rods

dominated bacterial biomass during the whole year, especially during

winter, covering 61 -72% of bacterial biomass (Fig. 2). During non-

winter period rods smaller than 0.5

µ

m

3

prevailed. Rods larger than

1

µ

m

3

dominated during winter. The importance of cocci increased

during warmer months when they accounted for up to 45% of

bacterial biomass. The majority of cocci biomass consisted of cells

with the volume between 0.01 -0.5

µ

m

3

. Filamentous bacteria covered

10 -24% of bacterial biomass. During the non-winter period, their

biomass mainly consisted of cells smaller than 1

µ

m

3

. During January

and December, a shift toward cells larger than 1

µ

m

3

occurred. In that

period, those cells covered up to 17% of bacterial biomass.

Fig. 1. Monthly distribution of bacterial biomass (mean ±1 SD)

(

µ

g C g

-1

).

Fig. 2. The contribution of different size classes of bacteria in bacterial

biomass (V= volume in

µ

m

3

).

Discussion

Bacterial biomass was one order of magnitude higher than values

reported in other coastal areas of the Mediterranean Sea (6). Our study

indicates annual patterns of bacterial biomass changes.

The size and shape of bacterial cells are affected by the conditions

in the environment. The quality and quantity of available organic

matter, temperature and grazing pressure, can provoke changes in cell

morphology. As opposite to water column, where protozoan predation

exerts a major in?uence on bacterial biomass, in benthic environments

grazing has no considerable impact on bacterial dynamics. According

to (7), the major parameter that determines the distribution of bacteria

and ?agellates in sediments is the size of sediment particles. The

decrease of sediment grain size is accompanied with decrease in

bacterial production and increase in ?agellate biomass. Therefore,

?agellates could have a stronger control over bacterial dynamics only

when bacterial production is minimal. In order to reveal the

importance of predation for bacteria in sediments of coastal Adriatic

Sea, it would be essential to elucidate the changes in bacteriovorous

protozoa abundance, as well as in benthic bacterial production. The

future investigations will focus on these problems.

References

1-Šimek, K.,Vrba, J., Pernthaler, J., Posch, T., Hartman, P., Nedoma, J.

and Psenner, R., 1997. Morphological and compositional shifts in an

experimental bacterial community in?uenced by protists with contrasting

feeding modes. Appl. Environ. Microb.,63: 587-595.

2-Holmquist, L. and Kjellember, S., 1993. Changes in viability,

respiratory activity and morphology of marine Vibrio sp. Strain S14 during

starvation of individual nutrients and subsequent recovey. FEMS

Microbiology Ecology, 12: 215-224.

3-Hobbie, J.E., Daley, R.J. and Jasper, S., 1977. Use of nucleopore filters

for counting bacteria by ?uorescence microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microb.,

33: 1225-1228.

4-Bratbak, G., 1985. Bacterial biovolume and biomass estimations. Appl.

Environ. Microb., 49: 1488-1493.

5-Norland, S., 1993. The relationship between biomass and volume of

bacteria. Pp. 303-309. In: P.F. Kemp, B.F. Sherr, E.B. Sherr, and J.J. Cole

(eds.), Handbook of methods in aquatic microbial ecology. Boca Raton,

Lewis Publishers.

6-Mirto, S., La Rosa, T., Danovaro, R. and Mazzola, A., 2000. Microbial

and meiofaunal response to intensive mussel-farm biodeposition in coastal

sediments of the western Mediterranean. Mar. Pollut. Bull.,40: 244-252.

7-Hamels, I., Muylaert, K., Casteleyn, G. and Vyverman. W., 2001.

Uncoupling of bacterial production and ?agellate grazing in aquatic

sediments: a case study from and intertidal ?at. Aquatic Microbial

Ecology,25: 31-42.