Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 37,2004

293

EXPERIMENTAL STRATEGIES RESPECTING DEEP-SEA CONDITIONS:

TOWARDS A RELIABLE MEASUREMENT OF THE IN SITU ACTIVITY OF DEEP-SEA PROKARYOTES

Christian Tamburini

1*

, Jean Garcin

1

, Francis de Bovee

2

, Laura Giuliano

3

and Armand Bianchi

1

1

Laboratoire de Microbiologie Marine, CNRS – INSU, COM, UMR 6117, Université de la Méditerranée, Campus de Luminy,

Marseille, France - * ctambu@com.univ-mrs.fr

2

OSU de Banyuls-sur-mer, CNRS-Université de Paris VI, Banyuls-sur-mer, France

3

Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Istituto dell’Ambiente Marino Costiero Sez. Messina, Italy

Abstract

High-pressure and low temperature conditions are the main characteristic of deep-sea environments. So, we developed special gears to

collect and incubate samples without decompression. Data from deep-seawater (1) as well as from deep hypersaline anoxic basins show

that each step involved in the organic matter degradation is carried out by prokaryotes adapted to the ambient conditions. Conversely

decompression of near-bottom water provokes an overestimation relative to the rates measured in situusing a benthic lander (2). Such an

opposite behavior facing pressure conditions is likely due to different origins of prokaryotes in the water column and at the water-sediment

interface.

Keywords: Microbial ecology of mesopelagic and bathypelagic zones; High-Pressure conditions; deep-sea prokaryotes

In deep-sea, prokaryotes are submitted to external factors (low

availability of nutrients, low temperature, high-pressure), all able to

limit their metabolism (4-9). Some environments, as the deep

hypersaline anoxic basins (DHABs) of the eastern Mediterranean,

offer even more severe conditions for life: hypersalinity (up to 300),

anoxia, extreme concentrations for Mg, SH

2

, and high pressure (~35

MPa). Therefore it is important to measure microbial activities in the

deep-sea as closely as possible to the in situconditions. So, we

developed special gears to collect and incubate samples without

decompression (Fig. 1).

Compiled data from stratified water columns show that each step

involved in the organic matter degradation is carried out by

prokaryotes adapted to the ambient pressure condition. Metabolic

rates measured on decompressed samples are underestimated by a

factor equal to 3.6

±

4.3 (mean

±

S.D.; n=99). Because the pressure

effect is highly variable, a single factor cannot be used to correct rates

measured on decompressed samples (1).

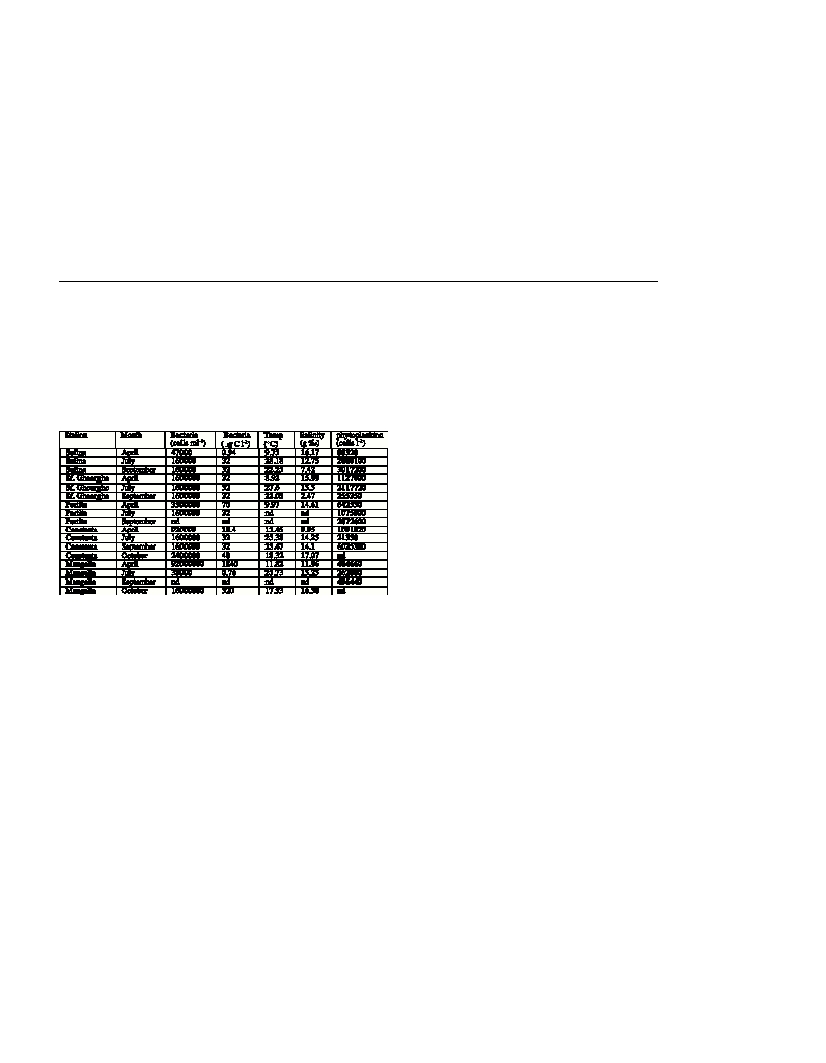

During the EU program BIODEEP (contract n°EVK3-2000-

00042), we measured diverse metabolic rates maintaining all the

characteristics of DAHBs during sample retrieval and incubation. All

the measured rates (peptidase, phosphatase, assimilation and

respiration of glutamate; bacterial biomass production) were higher

under ambient conditions (

×

12.5±23.6; mean ±S.D., n = 6) than

those obtained on the decompressed samples. Hence, we

demonstrated that DAHBs’prokaryotic populations are adapted to

extreme ambient conditions and may actively participate in the

biogeochemical cycles in these basins. Several strains of potential

industrial interest have been cultivated, some of which exhibiting very

unusual morphological and physiological features. Some newly

described bacterial catabolic genes with potential application in

bioremediation have also been retrieved and they are under

investigation.

Although decompression of deep-sea water and DHABs samples

leads to an underestimation of microbial activities, decompression of

near-bottom water samples provokes an overestimation (by 1 order of

magnitude) relative to the actual rates measured in situusing a benthic

lander (2). This apparent contradiction can be due to the difference in

origin for deep-sea water and benthic water microbial populations.

A large fraction of the bacterial consortia are transported into the

deep-sea by settling particles (9).

Since attached bacteria plays an important role in the

mineralization of particles (8, 10, 11) and in the recycling of biogenic

elements (silicate and carbonate), we did an experiment to simulate

the fall of particles through the whole water column. This experiment

demonstrates that metabolic rates of bacteria attached to the sinking

phytoplankton aggregates are slowed down by increasing pressure.

The gear we developed for this experiment will allow to precize

calculations for mineralization and dissolution rates of particles

sinking throughout the water column.

The experimental approaches we used to study deep-sea waters,

sinking particles and benthic waters, respecting the main conditions of

these deep-sea environments, and so permit to study the quantitative

and qualitative evolution of the chemical composition of the organic

matter, concomitantly with the evolution of microbial diversity, from

the sea surface to the bottom.

Reference

1-Bianchi, A., Tamburini, C. and Garcin, J., submitted. Effect of pressure

conditions on microbial activity measurements in deep-sea water: a

review. Deep-Sea Research I.

2-Tamburini, C., De Bovée, F. and Garcin, J. Microbial activities at the

deep-sea water-sediment interface of the NW Mediterranean: in situ

versus on board measurements. Journal of Geophysical Research.

3-Turley, C. and Lochte, K., 1990. Microbial response to the input of

fresh detritus to the deep-sea bed. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology,

Palaeoecology, 89: 3-23.

4-Poremba, K., 1994. Impact of pressure on bacterial activity in water

columns situated at the european continental margin. Netherlands Journal

of Sea Research,33: 29-35.

5-Yayanos, A.A., 1995. Microbiology to 10,500 meters in the deep-sea.

Ann. Rev. Microbiol,.49: 777-805.

6-Tholosan, O., Garcin, J. and Bianchi, A., 1999. Effects of hydrostatic

pressure on microbial activity through a 2000 m deep water column in the

NW Mediterranean Sea. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 183: 49-57.

7-Tamburini, C., Garcin, J., Ragot, M. and Bianchi, A., 2002.

Biopolymer hydrolysis and bacterial production under ambient hydrostatic

pressure through a 2000 m water column in the NW Mediterranean. Deep-

Sea Research II,49: 2109-2123.

8-Tamburini, C., Garcin, J. and Bianchi, A., 2003. Role of deep-sea

bacteria in organic matter mineralization and adaptation to hydrostatic

pressure conditions in the NW Mediterranean Sea. Aquatic Microbial

Ecology,32: 209-218.

9-Turley, C.M. and Mackie, P.J., 1995. Bacterial and cyanobacterial ?ux

to the deep NE Atlantic on sedimenting particles. Deep Sea Research I,42:

1453-1474.

10-Cho, B.C. and Azam, F., 1988. Major role of bacteria in

biogeochemichal ?uxes in the ocean’s interior. Nature,332: 441-443.

11-Smith, D. C., Simon, M., Alldredge, A. L. and Azam, F., 1992. Intense

hydrolytic enzyme activity on marine aggrgates and implications for rapid

particle dissolution. Nature,359: 139-142.

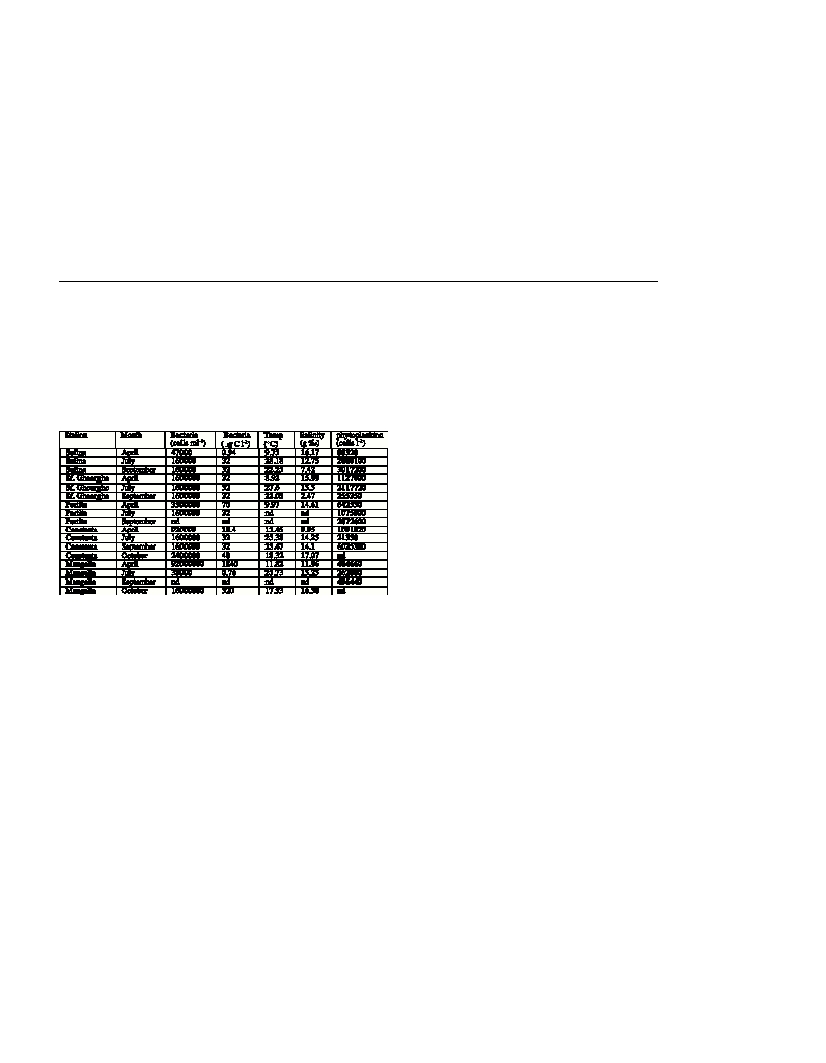

Fig. 1. Diagrammatic representation of the high-pressure bottles (HPBs)

in configuration of samples filling

When the filling valve is opened, the natural hydrostatic pressure pushes

down the ?oating piston and the seawater enters into the upper chamber of

2 HPBs. The distilled water is ?ushed out from the lower chamber of the

syringes to the exhaust tanks, through a nozzle that acts as an hydraulic

brake. During retrieval, hydrostatic pressure is maintained thanks to a check

valve that avoids any decompression within the ‘high pressure’ HPBs, in

contrast to the ‘decompressed’ one without check valve (8).