SEASONAL DIFFERENCES IN THE GROWTH OF PILCHARD SARDINA PILCHARDUSLARVAE

IN THE CATALAN SEA (NW MEDITERRANEAN).

I.A. Catalán, M.P. Olivar *, I. Palomera, E. Berdalet, C. Roldán and B. Aguilera

Institut de Ciències del Mar, Barcelona, Spain - * polivar@icm.csic.es

Abstract

The long- and short-term growth of 3.5 to 16 mm standard length Sardina pilcharduslarvae was compared between two cruises conducted

in autumn and winter in the Catalan Sea (NW Mediterranean). Growth was significantly higher in November than February, as assessed

by muscle fibre recruitment and RNA/DNA ratios. Otolith age-length relationships suggested a similar trend. Sea temperature is regarded

as a plausible explanatory factor for the differences in growth.

Keywords: Sardina pilchardus, larvae, growth, NW Mediterranean, temperature

Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 37,2004

330

Peak spawning of Sardina pilchardus in NW Mediterranean occurs

in the unstable autumn-winter season (1). Although variations in

environmental factors are known to affect both distribution and

abundance of pilchard larvae in this area (2, 3), there is little

information on the possible effects of environmental conditions on

larval biological parameters and their possible relationship to survival.

The objective of the present study was to test the hypothesis that

long- or short-term growth does not differ between two seasons

(autumn and winter) characterised by marked differences in mean

water temperature and comparable mean concentrations of potential

food items.

Two cruises were conducted, in the Catalan Sea in November 1998

and February 1999. Long-term growth was estimated by (a) age-

length relationships, and (b) the variation of fast muscle fibre

numbers. The rationale for the latter method, seldom used in field

studies, is that small differences in environmental variables

(particularly temperature) during egg and early larval stages are

known to alter muscle hyperplasia and/or hypertrophy, thus modifying

larval growth (4, 5). Short-term growth was assessed through

RNA/DNA ratios, based on the method described by Deniel (6).

Mean sea surface temperature in November 1998 (Mean=19.2ºC,

SE=0.007) was

about 6

°

C higher

than in February

(Mean=12.9ºC,

SE=0.07)). The

analysed larvae

were collected

from areas where

the median values

of copepod nauplii

were between 4.4

nauplii l

-1

(Nov-

ember) and 6.3

nauplii l

-1

(Feb-

ruary). The vertical

profiles of mean

temperature in the

depth-range inhabited by pilchard larvae (2) showed a strong

thermocline in November. It is believed that relative temperature

differences between cruises were maintained during all

developmental history of the larvae (based on AVHRR data: 7).

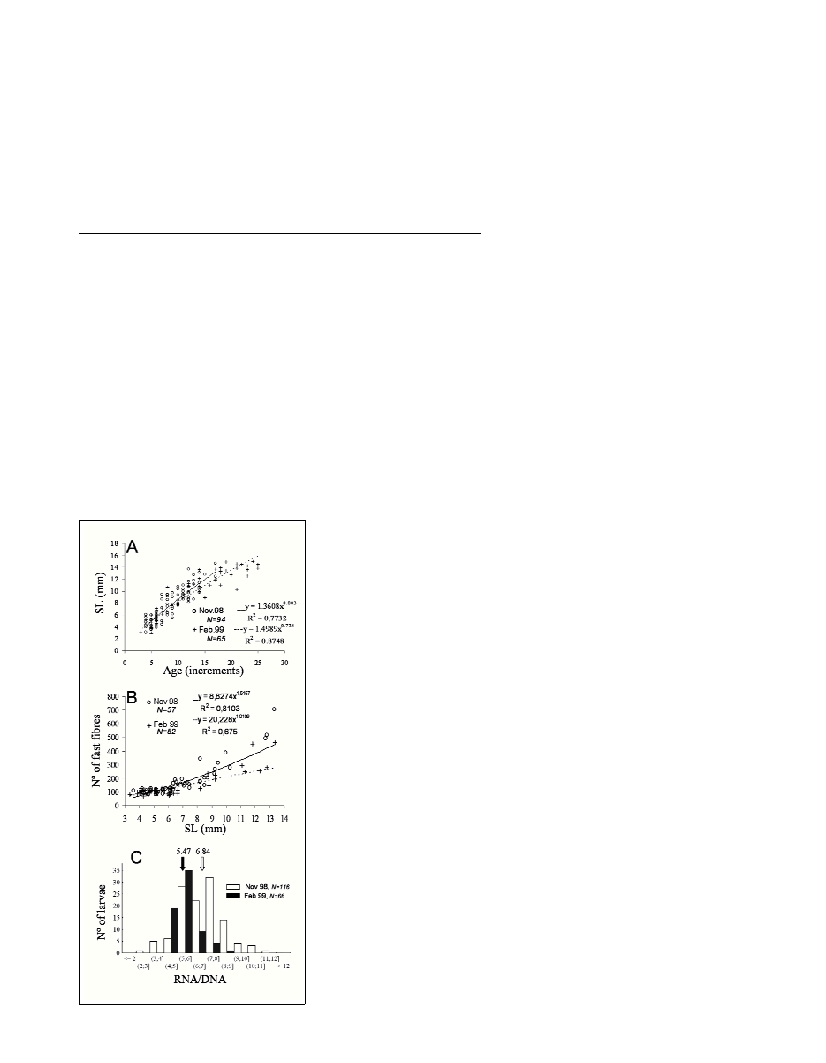

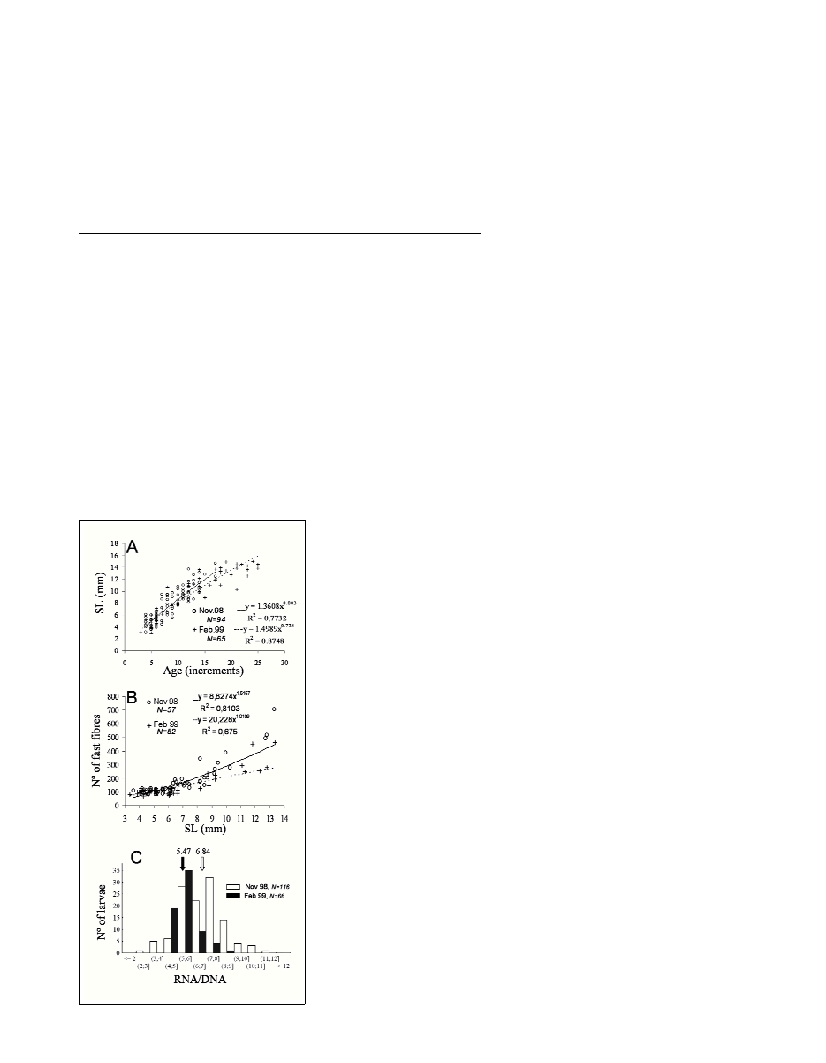

Long-term measures of growth indicated that pilchard larvae

exhibited higher growth rates in November than in February. For both

otolith and muscle-derived data, the slopes of the regression lines

were compared between periods by testing the significance of the

interaction term in a crossed two-way ANOVA with covariates (age or

length) performed on appropriatedly standardised variables for GLM

analysis. Although no significant difference in the slopes could be

established between cruises for the age-length data at an

a

=0.05, the

qualitative observation of the data (Fig 1A) suggest that November

larvae tended to be younger (faster-growing) for a given length (Fig.

1 A). This hypothesis is strengthened by the significantly higher

recruitment of fast muscle fibres in November respect to February

(Fig. 1B), as shown by the significant interaction term in the ANOVA

(interaction term: “year x total length” length used as a covariate,

F

1,106

=13.43, p<0.001).

The median RNA/DNA ratio in November was also significantly

(Mann-Whitney W=4174, p<0.0001) higher than in February, which

reinforces the results of the long-term growth analyses (Fig. 1C).

It is concluded that the 6ºC difference in temperature between the

two periods could account for the observed higher growth estimates in

November than in February. However, the effect of changes in species

composition of potential prey in February, related to the long

persistence of a mesoscale eddy near the study area (7), cannot be

ruled out. The slower growth of winter-spawned larvae could have

negative consequences for survival to juvenile stages. Individuals

would remain longer in the planktonic phase, which as noted elswhere

(8) could increase the predator-induced accumulated mortality.

References

1-Palomera I., Olivar MP., 1996. Nearshore ichthyoplankton off the

Costa Brava (Northwest Mediterranean). Bol. Inst. Esp. Oceanogr., 22:

71-76.

2-Olivar MP., Salat J., Palomera I., 2001. Comparative study of spatial

distribution patterns of the early stages of anchovy and pilchard in the NW

Mediterranean Sea. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser., 217: 111-120.

3-Olivar MP., Catalán IA., Emelianov M., and Fernández de Puelles ML.,

2003. Early stages of Sardina pilchardusand environmental anomalies in

the NW Mediterranean. Est. Coast. Shelf Sci., 56: 609-619.

4-Stoiber W., Haslett JR., Sänger A.M., 1999. Myogenic patterns in

teleosts: what does the present evidence really suggest? J. Fish Biol., 55:

84-99.

5-Johnston IA., Temple GK., Vieira VLA., 2001. Impact of temperature

on the growth and differentiation of muscle in herring larvae. Pp. 99-120.

In: Thorndyke D.A.M.. (ed), Environment and Animal Development:

Genes, Life Histories and Plasticity. BIOS Scientific Publishers Ltd.,

Oxford.

6-Berdalet E., 2002. Quantization of nucleic acids in marine

microplankton samples Pp. 271-289. In: Pelagic Ecology Methodology.

Subba Rao D.V. (ed). A.A. Balkema publishers.

7-Pascual A., et al.,2000. Detection by altimetry and AVHRR images of

fan intense anticyclonic eddy in the Balearic Sea. Proc. Int. Soc. Opt. Eng.,

4172: 31-36.

9-Hunter, J.R., 1981. Feeding ecology and predation of marine larvae.

Pp. 34-77. In: Lasker, R. (ed), Marine fish larvae: morphology, ecology

and relation to fisheries, Univ. of Washington Press, Seattle.

Fig. 1.

Comparison of long

and short-term

growth of Sardina

pilcharduslarvae in

November 1998 and

February 1999. (A)

Relationship

between estimated

age and standard

length. (B)

Relationship

between standard

length and total

number of fast

fibres, per

transverse section

of myotomal

muscle. (C)

Frequency

distributions of

RNA/DNA ratio

values. Arrows

indicate medians.