INITIAL PHASE OF THE INTRAOVARIAN SPERM STORAGE OF HELICOLENUS DACTYLOPTERUS

Sílvia Vila*, Maria Sàbat, Marta Muñoz and Margarida Casadevall

Àrea de Zoologia, Departament de Ciències Ambientals, Universitat de Girona, Campus Montilivi, Girona, Spain

* silvia.vila@udg.es, maria.sabat@udg.es, marta.munyoz@udg.es, margarida.casadevall@udg.es

Abstract

Sperm storage crypts located within the ovaries of Helicolenus dactylopterus were analysed during the first phase of this storage. Electron

and optical microscope observations showed some degree of organization of the stored spermatozoa. Besides, desmosomic unions among

cryptal cells denoted the isolation of spermatozoa inside the crypts and were probably related to the protection of these cells from the

immune system of the female.The retainment of an important portion of cytoplasm by the spermatozoa at the beginning of the storage

could be explained as an initial source of nutrients while there is not nutritional supply from the female.

Key words: Helicolenus dactylopterus, sperm storage, histology, ultrastructure

Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 37,2004

456

The bluemouth rockfish, Helicolenus dactylopterus, is a zygo-

parous oviparous species with internal fertilization. Females present

specialized structures known as crypts where the spermatozoa are

stored and mantained viable for periods up to 10 months, from April

and May onwards. When spawning starts, between January and

February, the spermatozoa stored in the crypts must be reactivated,

with subsequent fertilization of mature eggs (1).

We found that Helicolenusdacctylopterusshows the most complex

structures for sperm storage than those previously described in

viviparous species within the same family (2-3). Thus, in this species

spermatozoa remain grouped within differentiated structures instead

of ?oating freely like in Alcichthysalcicornis (3) or singly adhered to

the ovarian epithelium as found in viviparous species like Sebastes

taczanowskiithat retain spermatozoa adhered to the epithelium of the

ovigerous lamella or wrapped in its microvilli. The prolonged time

period during which spermatozoa must reside in the ovary may offer

an explanation about the existence of these specialised storage crypts.

The aim of this paper is to analyze the structure and ultrastructure

of these intraovarian crypts during the initial period of storage. From

June onwards there is a marked increment of testicular activity (4),

thus our work has been focused on two fresh samples caught in July

(Palamós, Costa Brava, northwest Mediterranean), when the crypts

are full of “new” spermatozoa.

In both cases several portions of the central ovarian area were

analysed. Small pieces of ovary were fixed in glutaraldehyde (2.5%)-

paraformaldehyde (2%) mixture in a 0.1 M cacodylate buffer.

Spermatozoa storage structures are located very near the muscular-

connective rachis of the gonad, at the base of the interlamellar gaps

(5). The cryptal epithelial cells present a nucleus with some strongly

condensed heterochromatin, a lot of free ribosomes, vesicles and

RER, and this is a clear evidence of important protein synthesis.

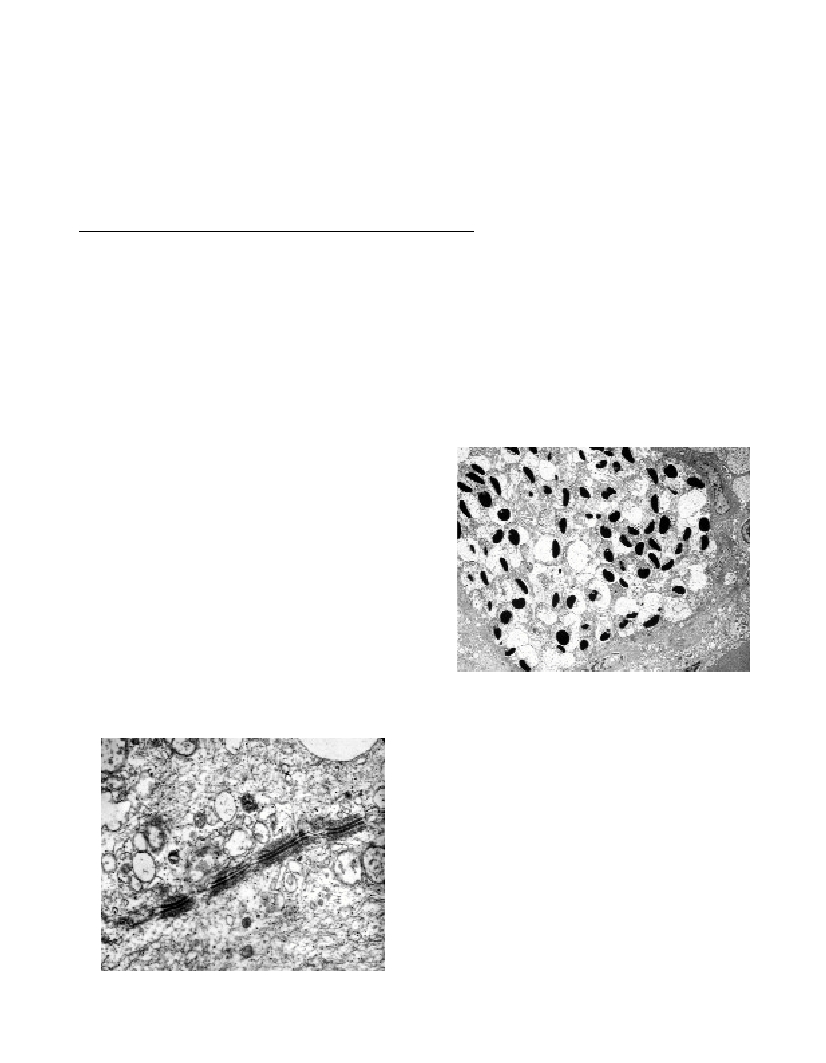

We also observed an enormous quantity of desmosomal unions

among the cryptal cells (Fig. 1), forming thus a continuous cellular

layer that surrounds the crypt cavity, probably related to the protection

of the spermatozoa from the immune system of the female which

stores them (3). Lining the epithelial cells there are some cells of

different morphology, with a nucleus slightly extended and much

more electrodense.

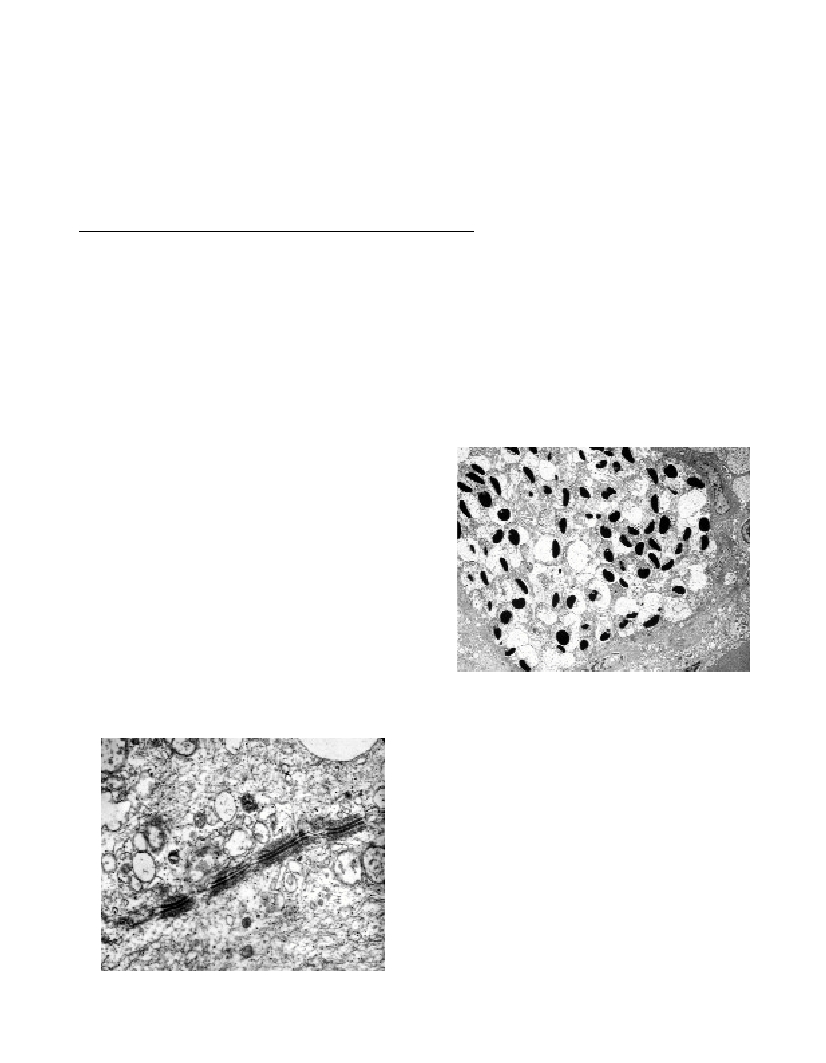

Our observations through the optical microscope suggested some

organization of the male gametes located in the crypts, a fact that later

was corroborated by the transmission electronic microscope. We can

clearly see that these organizations are not due to the existence of a

separate membrane like the ones which surround spermato-

zeugmata.(6), but the spermatozoa are arranged in some kind of bun-

dles seemingly independent one from one another.

An outstanding fact is that the spermatozoa remaining inside the

crypts keep an important portion of cytoplasm (Fig. 2), in which we

can observe many mitochondria, vacuola and tiny granules. A possible

explanation could be that this cytoplasm represents an initial reserve

of nutrients for spermatozoa at the beginning of the storage period,

while later there would be evidence of a supply of nutritional

substances from the female towards the male sexual cells, a fact that

we aim to confirm in further studies.

References

1-Muñoz M., Casadevall M., Bonet S.,1999. Annual reproductive cycle

of Helicolenus dactylopterus dactylopterus (Teleostei: Scorpaeniformes)

with special reference to the ovaries sperm storage. J. Mar. Biol. Ass. UK.

79:521-529.

2-Moser, H.G. 1967. Seasonal histological changes in the gonads of

SebastodespaucispinisAyres, an ovoviviparous teleost (family

Scorpaenidae). J. Morphol. 123: 329-354.

3-Koya Y., Munehara H.,and Takano K., 1997. Sperm storage and

degradation in the ovary of a marine copulating sculpin, Alcichthys

alcicornis(Teleostei: Scorpaeniformes): role of intercellular junctions

between inner ovarian epithelial cells. JMorphol. 233: 153-163.

4-Muñoz, M. and M. Casadevall 2002. Reproductive indices and

fecundity of Helicolenus dactylopterus dactylopterus(Teleostei:

Scorpaenidae) in the Catalan Sea (western Mediterranean). J. Mar. Biol.

Ass. U.K. 82: 995-1000.

5-Muñoz M., Casadevall M., Bonet S.,and Quagio-Grassiotto I., 2000.

Sperm storage structures in the ovary of Helicolenus dactylopterus

dactylopterus(Teleostei: Scorpaeniformes): an ultrastructural study.

Environmental Biology of Fishes. Kluwer Academic Publ., Netherlands.

58: 53-59.

6-Downing, A. L. and J. R. Burns (1995). Testis morphology and

spermatozeugma formation in three genera of viviparous halfbeaks:

Nomorhamphus, Dermogenys, andHemirhamphodon (Teleostei:

Hemiramphidae). Journal of Morphology. 225: 329-343.

Fig. 1. Transmission electron micrograph showing desmosomal unions

among cryptal epithelial cells.

Fig. 2. Intraovarian sperm storage crypts. Electron microscopy view

showing a sperm bundle surrounded by cryptal epithelial cells.