RECOVERY AFTER ANTHROPOGENIC DISTURBANCE: EARLY EFFECT OF PROTECTION

ON RECOVERY PATTERNS OF HARD SUBTIDAL SESSILE ASSEMBLAGES

Stanislao Bevilacqua

1

, Antonio Terlizzi

1*

, Simonetta Fraschetti

1

, Giovanni Fulvio Russo

2

1

Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie Ambientali, Università di Lecce, CoNISMa, Lecce, Italy - stanislao.bevilacqua@unile.it

2

Istituto di Meteorologia e Oceanologia, Università di Napoli “Parthenope”, Napoli, Italy

Abstract

A manipulative experiment was conducted to explore the effect of protection on recovery dynamics of hard subtidal sessile benthic

assemblages affected by date mussel (Lithophaga lithophaga) fishery. Preliminary results showed that the recovery of disturbed

assemblages was faster in the protected location than in controls. However, the study underlines the need for long-term monitoring

experiments in any attempt to assess the potential role of marine protected areas in mitigating the negative effects of human disturbance

on coastal biota.

Key words: date mussel fishery, subtidal habitat, multi-layer assemblages, recovery dynamics, MPA

Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 37,2004

493

Introduction and methods

Date mussel (Lithophaga lithophaga) fishery (DMF) is one of the

most harmful anthropogenic activities affecting hard subtidal benthic

assemblages in the Mediterranean Sea (1, 2). Despite of this, little is

known on recovery dynamics of assemblages in patches disturbed by

DMF. On April 2003, we started a manipulative experiment

simulating DMF damage at three locations at Punta Campanella

(Campania, SW Italy). One of these was located inside a no-take, no-

access marine protected area, the other two random-chosen locations

served as controls. At each location, six plots were randomly

individuated on subvertical rocky walls at 4-6 m depth, three of these

were treated and three served as unmanipulated controls. Few days

later, a photographic sampling was carried out providing n=5

replicates for each plot. Samples were examined by visual estimates

evaluating cover percentage and number of taxa (3).

Results

DMF caused, on average, a decrease of 75% of the average values

of total cover recorded in controls and 1/6 of the total number of taxa

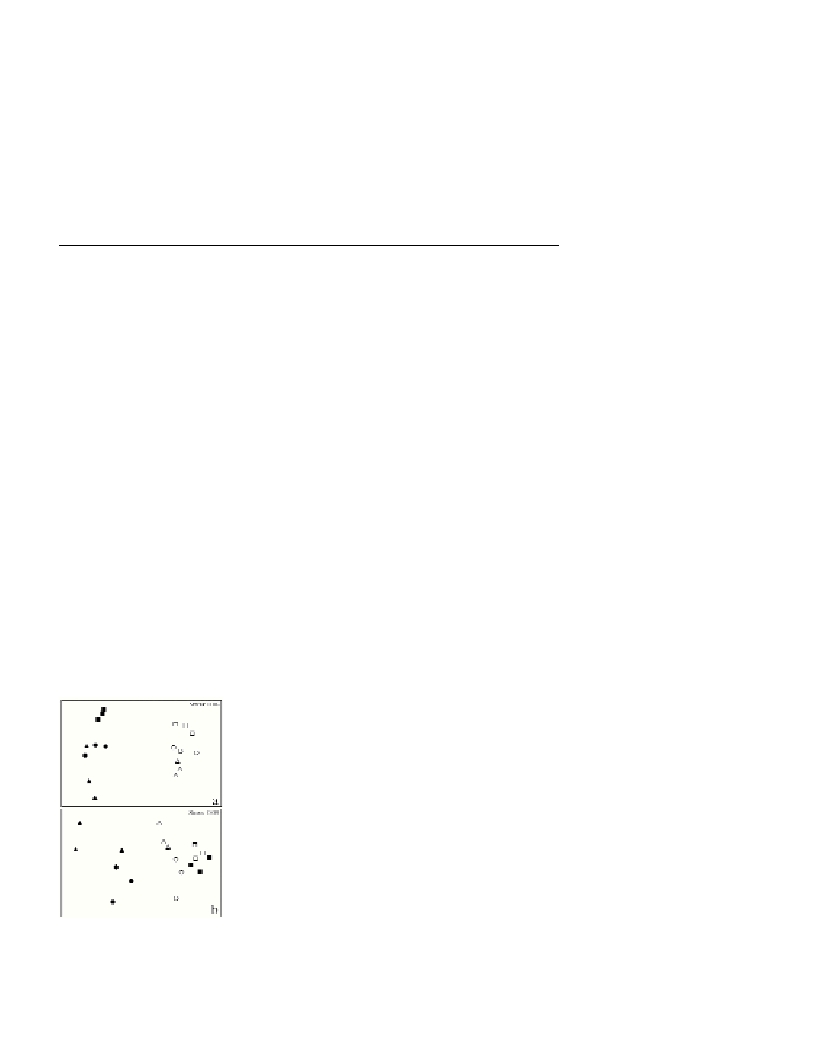

completely disappeared in manipulated plots. The nMDS ordination

of the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity values (Fig. 1a) well separated

treatments but also portrayed differences among locations within

treatments. Multivariate analyses also revealed that erect algae,

massive sponges, vermetids, hydroids and colonial ascidians mostly

contributed to separate disturbed and undisturbed assemblages, thus

indicating a strong impact of DMF on these taxa. Encrusting and

cryptic organisms were apparently less affected by DMF as indicated

by their low contribution to the values of dissimilarity between

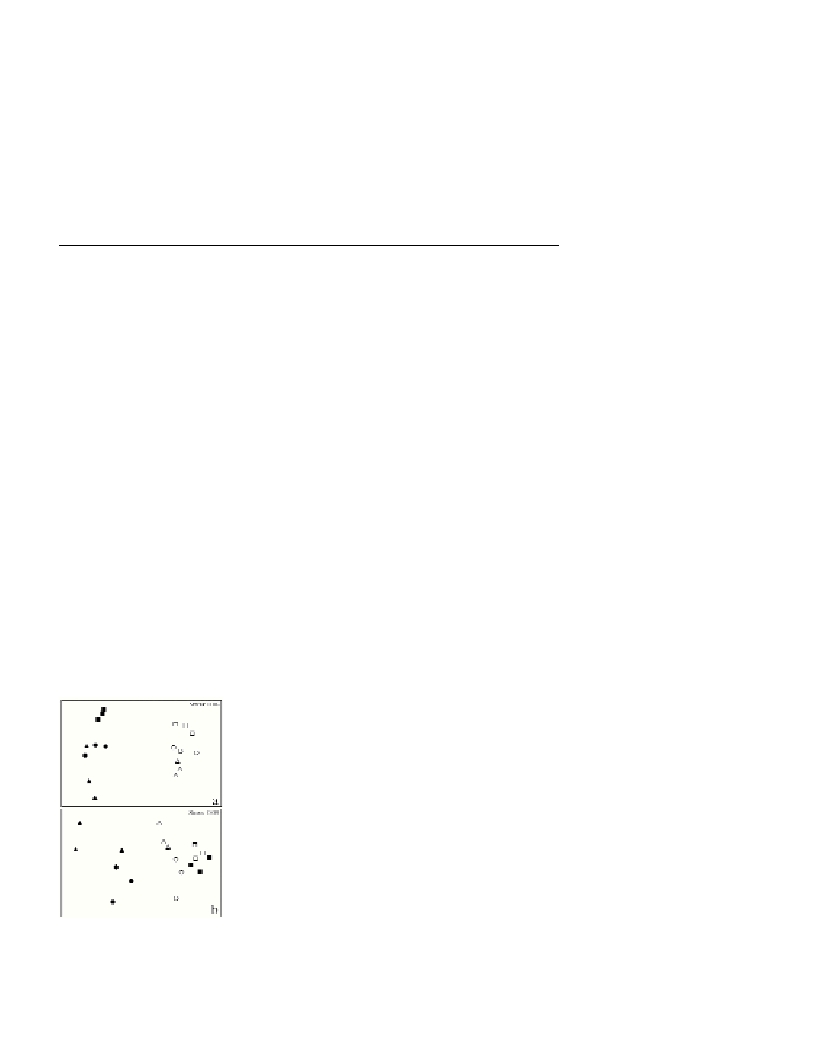

disturbed and undisturbed assemblages. The nMDS ordination of data

from the second time of sampling (July 2003) showed that

manipulated plots in the protected location aggregated with their

respective unmanipulated plots, whilst in control locations

manipulated and unmanipulated plots were still clearly separated

(Fig.1b).

Discussion and conclusion

Local factors could be considered of greater importance in driving

recovery dynamics, especially when DMF allows the survival of small

colonies and create relative small embedded patches as in our case. In

such a situation, vegetative propagation from neighbours and residual

pool of taxa escaped to complete destruction may exert an important

role in recovery of disturbed assemblages (4). Thus, the importance of

differences in growth rates and interspecific relations among the

involved taxa could rise against external factors (e.g. larval supply)

that, instead, could have a central role when larger areas of substrate

are heavily affected by DMF (5). The ecological mechanisms driving

an apparently faster recolonization in protected locations are still

unknown. Our results suggest that protection has a critical effect on

recovery dynamics. This effect tends to accelerate the recovery

without changing the structure of pre-existing assemblages.

Paradoxically, erect algae, that experienced the greatest DMF impact,

were those that recovered faster and mostly contributed to similarity

between disturbed and undisturbed assemblages in the second time of

sampling but, under the canopy, the other layers of assemblages are

far from pristine conditions. It is unlikely that in the protected location

assemblages as a whole had recovered completely, due to differences

in life cycles, growth rates and distribution of organisms across layers

in multi-stratified systems (6). Turf regains space very quickly after

disturbance (7) but encrusting and cryptic organisms could be much

slower in recovering. Thus, DMF disturbance could act differently

across layers, and the recovery of the whole assemblage could occur

over a longer period than what needed by the turf layer. Moreover,

seasonality and the time of disturbance’s occurrence could have

significant outcomes on recovery. This study is, therefore, still in

progress to monitor the temporal trend of recovery over a longer-time

period. Since the integrity of benthic communities is crucial for

coastal ecosystems, a deeper understanding of recovery dynamics in

areas damaged by DFM with the use of long-term experimental

monitoring is needed to integrate the preventive action of authorities

with an effective policy of mitigation of human impact on coastal

zone.

References

1 - Fanelli G., Piraino S., Belmonte G., Geraci S., and Boero F., 1994.

Human predation along Apulian rocky coasts (SE Italy): desertification

caused by Lithophagalithophaga(Mollusca) fisheries. Mar. Ecol. Prog.

Ser.,110: 1-8.

2 - Naylor E., 1995. Marine Biology. P. 212. In:Encyclopaedia Britannica

Yearbook 1995. Encyclopaedia Britannica Inc., London.

3 - Dethier M.N., Graham E.S., Cohen S., and Tear L.M., 1993. Visual

versus random-point percent cover estimations: ‘objective’is not always

better. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser.,96: 93-100.

4 - Sousa W.P., 2000. Natural disturbance and the dynamics of marine

benthic communities. Pp. 85-130. In:M.D. Bertness, S.D. Gaines and

M.E. Hay (eds), Marine community ecology. Sinauer Associates Inc.,

Sunderland, Massachusetts.

5 - Connell J.H., and Keough M.J., 1985. Disturbance and patch dynamics

of subtidal marine animals on hard substrata. Pp. 125-151. In:S.T.A.

Pickett and T.S. White (eds), The ecology of natural disturbance and patch

dynamics. Academic Press, Orlando, FL.

6 - Airoldi L., 2000. Responses of algae with different life histories to

temporal and spatial variability of disturbance in subtidal reefs. Mar. Ecol.

Prog. Ser.,195: 81-92.

7 - Airoldi L., 2000. Effects of disturbance, life histories, and overgrowth

on coexistence of algal crusts and turfs. Ecology, 81: 798-814.

Figure 1a,b.

Non-metric multidimensional

scaling ordinations based on

Bray-Curtis dissimilarity

values of plots’ centroids

(untransformed data).

(a) 1°Time; (b) 2°Time.

Squares = protected location,

Circles = Control location 1,

Triangles = Control location 2;

manipulated plots = filled

symbols, unmanipulated plots =

empty symbols.