MAPPING DISTRIBUTION OF BIODIVERSITY IN MARINE RESERVES

Paolo D’Ambrosio, Giuseppe Guarnieri, Simonetta Fraschetti

*

, Antonio Terlizzi, Simona Bussotti

Dipartimento di Scienze e Tecnologie Ambientali, Universitŕ di Lecce, CoNISMa, Lecce, Italy – giuseppe.guarnieri@unile.it

Abstract

An adequate knowledge of habitat and assemblage distribution has important consequences in conservation and management of Marine

Protected Areas. A fine-scale study of two MPAs located in Apulia is here reported to analyse existing protection schemes and to assess if

habitats and communities are properly represented in the differently protected zones and if the no-take and no-access zones are

representative of the general reserve. Results emphasize that, at present, zoning is totally arbitrary in both MPAs with the consequences

that detailed information on the distribution of the biota could greatly increase current zonation patterns.

Keywords: Marine Protected Areas, zoning plan, biodiversity, GIS

Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 37,2004

509

Introduction and Methods

A number of papers have already discussed the general lack of

baseline information on biodiversity distribution in coastal marine

habitats and especially within Marine Protected Areas (1, 2). This

general lack of knowledge has important consequences since it

prevents either an adequate zoning schemes and the potential iden-

tification of networks of habitatand communities representative at

regional scale (3). A better knowledge in this field might also avoid

possible sources of habitat confounding when experimental designs

needing the selection of appropriate controls are used to demonstrate

effectiveness of protection.

The aim of the paper is to map the distribution of habitat and

communities in order to assess if they are properly represented in the

differently protected zones and if the no-take and no-access zones are

representative of the general reserve.

Data are reported from a series of extensive field surveys carried out

in last the three years in the MPAs of Torre Guaceto and Porto Cesareo

(Apulia, Italy). Both MPAs are divided in three zones (namely: A, B,

C) varying with respect to the degree of restriction of human activities.

Here direct observation methods, such as beach transects and SCUBA

diving surveys (using global position system GPS)were adopted. Data

were then imported in a GIS to create thematic maps.

Results

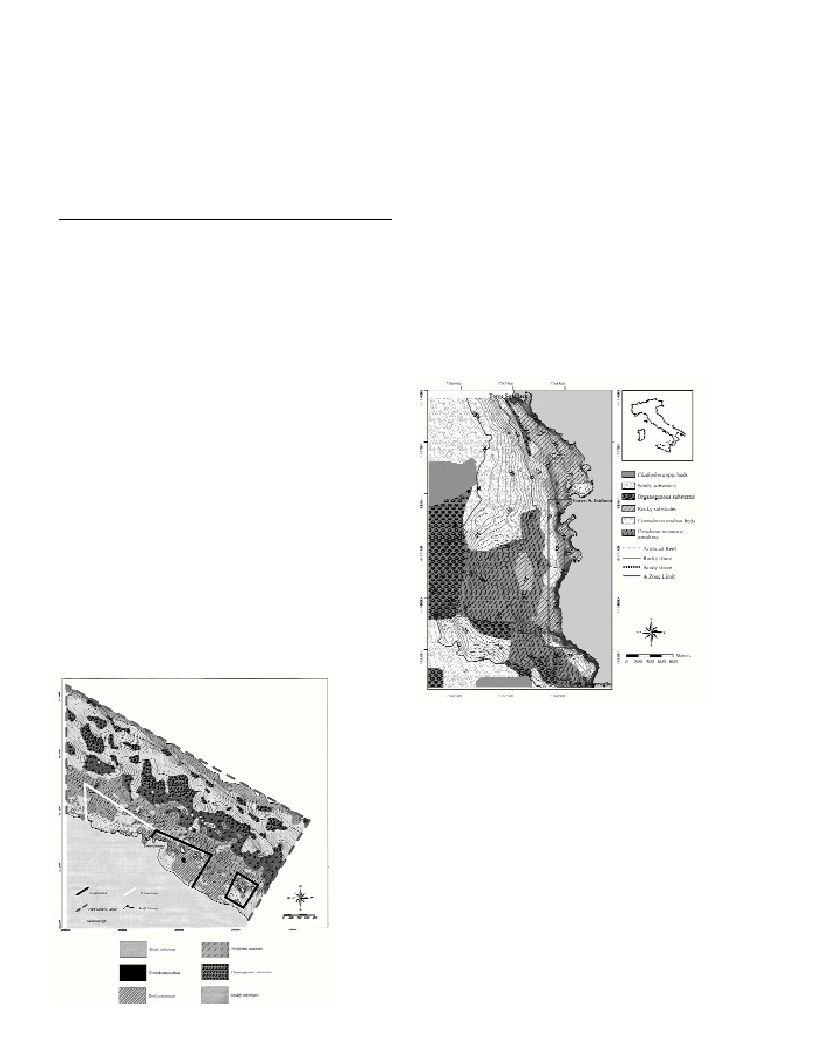

The MPA of Torre Guaceto (40°42’N; 17°48’E) has a surface of

about 2.207 ha and is embedded within a human-dominated

landscape. This MPA exhibits complex spatial patterns being

characterized by a set of very different habitats (from bioconstructors

to seagrasses). However, the proportion of habitat types targeted for

full protection is not adequately represented. The lack of an adequate

knowledge before the institution prevented appropriate decisions

about reserve boundaries, with the consequences that preco-

ralligenous and coralligenuos formations and Posidoniaoceanica

meadows are not included in the no-take no access zone (Fig. 1).

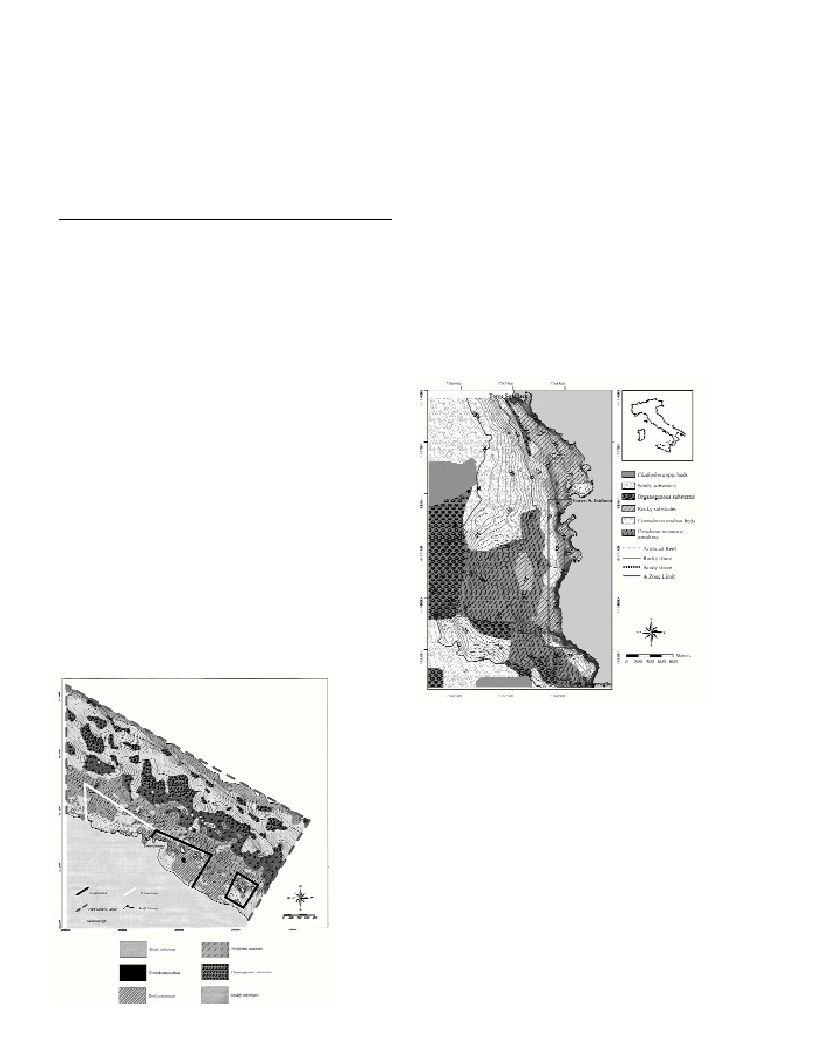

The MPA of Porto Cesareo (40°14’N; 17°54’E) has an extension of

16.654 ha. It is a small village with intense turistic activities. Results

show that also in this case sea grasses and coralligenous formations are

excluded from the no-take no access zone. Several other self-contra-

dictions emerge. The date mussel Lithophaga lithophagafishery, albeit

prohibited, is very active inside the MPA, with the result that the extent

of desertified seascape is continuously increasing and one of the most

represented community is that of sea urchin barrens. Moreover, a sew-

age outfall and a fish and mussels aquaculture farm are located within

the MPA in proximity of the integral protection zones and a sandy

beach with free access is within the no-take no access zone (Fig. 2).

Discussion and Conclusion

In both cases, results emphasize that present zoning is totally

arbitrary and collected data provide different scenarios for a correct zo-

ning plan able to include both ecological and socio-economic aspects.

Thus, large-scale mapping even if are costly and time-consuming,

allow managers to visualise the spatial distribution of habitats, thus ai-

ding the planning of networks of marine protected areas and allowing

the degree of habitat fragmentation (in the case of Porto Cesareo deter-

mined by the date mussel fishery) to be monitored. As Gray states (4),

a mosaic of marine habitats must be protected if complete protection of

biodiversity is to be achieved. Representative samples of species and

assemblages distinctive of a particular locality or region should be

included within reserve boundaries to grant their long-term persistence.

References

1-Cabeza, M., Moilanen, A., 2001. Design of reserve networks and the

persistence of biodiversity. Trends in Ecology and Evolution, 16, 242-248.

2-Villa F., Tunesi L., Agardy T., 2002. Zoning Marine Protected Areas

through Spatial Multiple-Criteria Analysis: the Case of the Asinara Island

National Marine Reserve of Italy. Conservation biology16 (2), 515-526.

3-Sala E., Oropeza O., Paredas G., Parra I., Barrera J.C., Dayton P.K.,

2002. A general model for designing networks of marine reserve. Science,

298: 1991-1993.

4-Gray, J.S., 1997. Marine Biodiversity: Patterns, threats and

conservation needs. Biodiversity and Conservation6, 153-175.

Fig. 1.

Map of the Marine

Protected Area of

Torre Guaceto.

Fig. 2.

Map of the

Marine Protected

Area of Porto Cesareo.