ECOLOGICAL STRUCTURE AND DYNAMICS OF THE SEAGRASS CYMODOCEA NODOSA

IN MONTAZAH BAY OFF ALEXANDRIA, EGYPT

S. H. Shabaka

1*

, H. M Mostafa

2

H. Mitwally

2

, Y. Halim

2

1

National Institute of Oceanography and Fisheries, Alexandria, Egypt

2

Department of Oceanography, Faculty of Science, University of Alexandria, Egypt - youssefhalim@hotmail.com

Abstract

Cymodocea nodosawas sampled from different sites located within a seagrass bed in Montazah Bay, Alexandria, Egypt. Samples were

collected at bimonthly during the period from February 2002 to December 2002. Physico-chemical parameters were measured in

conjunction with seagrass phenological parameters. Generally, all phenological parameters except rhizome-root biomass showed

maximum values in late spring (June), and minimum values during winter. Rhizome-root biomass, showed an opposite trend. It was

concluded that although light and temperature are the major factors controlling seasonality of C. nodosa growth, during summer the growth

is limited by other factors, mainly self-shading and nutrient limitation. Five environmental factors were identified as important in

controlling biomass and abundance of C. nodosa. These include temperature, salinity, light, water and sediment nutrient concentrations.

Qualitative determination of associated epiphytes was also performed.

Key words: Seagrasses; Cymodocea nodosa; Montazah; Alexandria; Egypt

Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 37,2004

550

The presence of the two species of seagrasses Posidonia oceanica

and Cymodocea nodosaalong the Egyptian Mediterranean waters is

largely documented (1, 2,3, 4). Along Alexandria coastal waters,

many beds have been badly damaged and seagrasses are reduced to

scattered patches in inshore semi-closed bays. In front of Alexandria,

seagrass beds are exposed to untreated wastewater pollution and

turbidity. Growth of C. nodosais continuous throughout the year with

a unimodal cycle. Its foliage started to increase toward spring and

became particularly dense in late spring (June), with maximum-

recorded shoot density (131shootsm

-2

±44) and leaf density (368

leafm

-2

±473). These values decreased towards summer. Minimum

shoot and leaf densities were recorded during winter (52 shootm

-2

±8,

113 leafm

-2

±13). Leaf area index, leaf length, epiphytic area,

photosynthetic area and leaf biomass showed the same cyclic pattern

as shoot and leaf densities. Rhizome-root biomass showed an opposite

cyclic pattern to the other phenological parameters, where maximum

values were recorded during winter (23.4gm dwm

-2

±6), and

minimum values recorded June (4.7gm dwm

-2

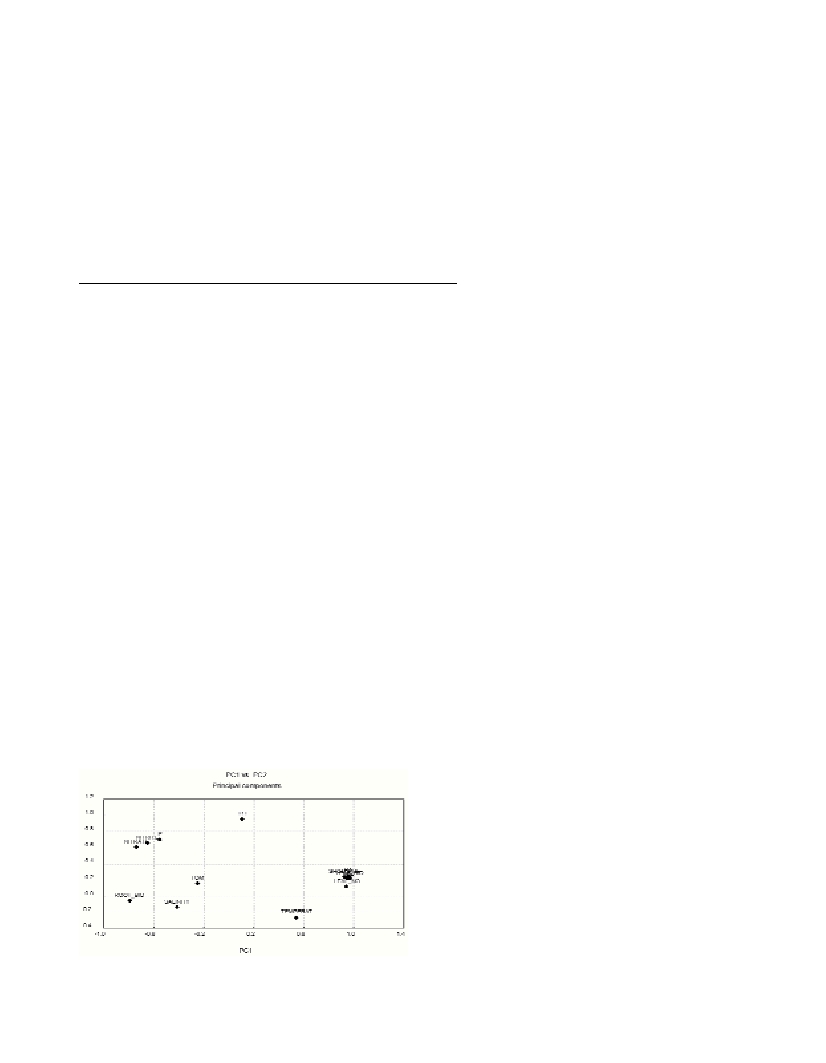

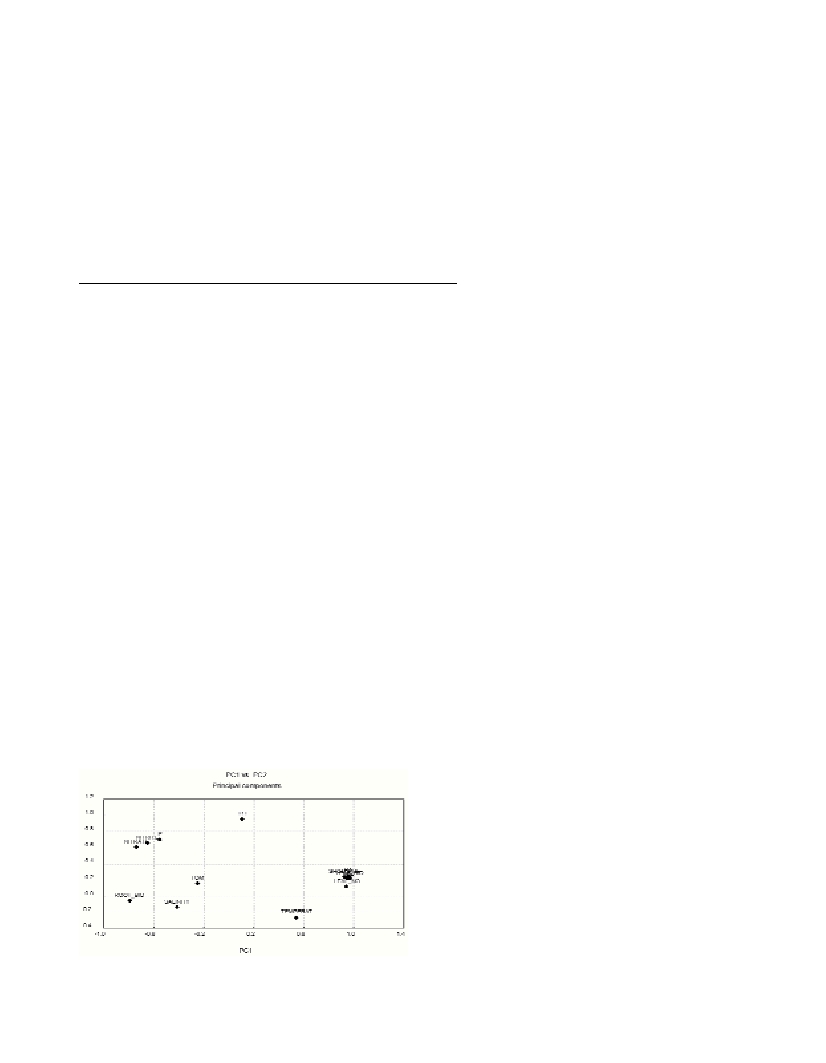

±2). Principal

component analysis was used for “C. nodosa phenological-

Physicochemical parameters relationship”. Plotting PC1 against PC2

(Fig.1) revealed that phenological parameters of the foliar system

had positive correlations with temperature and PH, and negative

correlations with dissolved nutrients and salinity and insignificant

correlation with total sediment organic matter (TOM). Root-rhizome

biomass showed completely opposite correlations to those of the

foliar system. Seasonal variation of the foliar system of C. nodosa

could probably be related to changes in temperature and light

availability. Changes in temperature over the year seem to play an

important role in the reproduction cycle of C. nodosa, which in?uence

the leaf growth and production (5). In the meadow under study, a male

?ower and seeds were recorded at the end of April. It seems to be that

seeds were dormant, buried in the sediment until germination started

in April, coinciding with the rise in water temperature. It was

observed that the potential production set by the incoming irradiance

and water temperature was not met during summer. This deviation

may be attributed to the following reasons: a)Increased epiphytic

growth on plant leaves in late spring. b)Self-shading by the plants,

where maximum leaf length was recorded during late spring. c)

Higher turbidity observed in the bay during summer d)Nutrient

limitation of summer growth, where minimum dissolved nutrient

concentrations was recorded during late spring. This may be attributed

to the active consumption of the seagrass to the dissolved nutrients.

The reduction of salinity due to intrusion of fresh water that may carry

high concentrations of dissolved nutrients caused the initiation of the

foliar system growth in late winter. The opposite correlation between

the underground biomass and foliar system biomass may be attributed

to the dependence of the rhizome and roots on the extensive foliar

system biomass during their growing season in absorption of the

nutrients from the surrounding water. After the collapse of the foliar

system that occurred in the summer season, rhizome and root system

started to increase in biomass to compensate the reduction of dis-

solved nutrients in seawater by absorption of the nutrients from the se-

diments. The sediment is the main source for phosphorus in carbonate

sediment seagrasses, the acquisition of phosphorus by both seagrasses

P. oceanica and C. nodosamight be limited by sparse supply in water

column and their ability of speeding up the uptake of phosphorus from

the sediments (6). In Montazah Bay, turbidity caused by water sports

and seagrass damaging are a threat to seagrass meadows. Despite

these destructive factors, C. nodosais a eurybiontic species tolerates

considerable ?uctuations in environmental variables. This may

explain the dominance of C. nodosaover the P. oceanicawhen the

conditions are unfavorable for the stenobiontic P. oceanica(4).

Cymodocea nodosa epiphytic associations:

Floral epiphytes: Blue green algae: Anacystis aeruginosa,

Oscillatoria lutea.Red algae: Audouinella thuretii, A. virgatula,

Bangia atropurpurea, Chroodactylon ornatum, Erythrocladia carnea,

Hydrolithon farinosum, Melobesia membranacea, Pneophyllum

fragile kuetzing, Porphyrostromium ciliare, Sahlingia subintegra,

Stylonema aslidii, S. cornu-cervi. Brown algae: Giraudia

sphacelarioides, Myrionema orbiculare. Green algae: Cladophora

socialis, Entocladia ?ustrae, Ulvella len(Personal comm. Prof.

Giusppe Giaccone).

References

1-Steuer, A., 1935. The fishery grounds near Alexandria. I-Preliminary

report. In notes and memories, no. 8 Cairo.

2-Aleem, A.A., 1955. Structure and evolution of the seagrass

communities Posidoniaand Cymodoceain the southern Mediterranean.

Essays in the natural science in the honor of Capitan Allan Hancock.

Univers. Of S. Calif. press Los Angeles, Calif., pp. 279-298.

3-Mostafa, H. M., 1996. Preliminary observations of the seagrass

Cymodocea nodosa(Ucria) Asherson in the Mediterranean waters off Ale-

xandria, Egypt. Bull. Nat. Inst. Of Oceanogr. & Fish., A. R. E., (22): 19-28.

4-Den Hartog, C., 1970. The seagrasses of the world. North- Holland

publishing Co., Amsterdam, 275 p.

5-Buia, M. L. Mazzella, 1991. Reproductive phenology of the

Mediterranean seagrass Posidonia oceanica(L.) Delile, Cymodocea

nodosa(Ucria) Ashers., and Zostera notliiHornem. Aquatic Botany,40 :

343-362.

6-Mostafa, H. M., 1997b. Phosphorus content in seagrass meadows of

Posidonia oceanica(L.) Delile andCymodocea nodosa(Ucria) Ashers off

Alexandria, (Egypt). A proceeding of the 7th International conference on

Environment protection is a must, 20-22 May, Alex, Egypt, (NIOF) and

(ISA) pp. 353-362.

Fig. 1. Components loadings matrix of phenological parameters (leaf

area index, leaf density, shoot density, photosynthetic area and epiphyt-

ic area and Physico-chemical parameters (salinity, temperature, PH,

TOM and dissolved inorganic nutrients).