Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 36,2001

22

Introduction

The Black Sea, one of the largest inland seas in the world lying at the

junction between Europe and Asia, is both oceanographically and geo-

logically unique because of its to anoxic layer below 100-150 m.

Although there is ex

c

e

s

s

ive supply of terrigenous sediment input in the

Black Sea, pelagic sedimentation plays the major role in the deep (1).

Since 1991 the group formed around the UNESCO/TREDMAR

Training-Through-Research (TTR) program has inve

s

t

i

gated the

Black Sea with the works of other groups. During these surveys, SIM-

RAD EM 12S low frequency multibeam and SEABAT echosounders

were used to obtain bathymetric charts and re?ectivity maps of the sea

?oor. In addition, MAK-1 deep-tow side scan sonar and subbottom

profiler system was used to get acoustic images of the sea?oor and the

shallow sediments. SIMRAD EM 12S multibeam echosounder oper-

ates at 13 kHz frequency and has an angular coverage of 1200 m. The

MAK-1 combined side scan sonar and subbottom profiler system has

a swath range of up to 500 m per side in long-range mode (30 kHz)

and up to 200 m per side in high-resolution mode (100 kHz). The high-

resolution subbottom profiler sections and the side scan sonar records

shown in this study were compiled from several TTR researches.

Turkish continental slope

Turkish Continental Slope of the Eastern Black Sea Basin, which

has a relatively smooth slope and deepens from 305 m to 1945 m.

depth, comprises of rectilinear gullies and V-like channels (2). In con-

trast with the concave Russian continental slope, the Turkish conti-

nental slope has a convex morphology.The slope gradient becomes

progressively steeper as it is traced downwards from the top, which is

the result of either mass movement or structural control. Maximum

slope angle detected is 12.6° (3). The slope is cut by only a small num-

ber of canyons and valleys, which are generally on a smaller scale than

those found on the Russian Continental Slope. The lower section of

the slope comprises relict slump structures overlain by a semi-contin-

uous surficial unit of parallel-bedded sediments. The middle section of

the slope exhibits a steeper gradient, and slump structures are observed

at the seabed here. The upper slope shows a zone of syn-sedimentary

thrust faults (the upslope side is down- thrown). The basin and the

canyons are a continuation of the Yesilir-mak River across the shelf to

the continental slope. The basin and the canyons deepen towards the

northwest.

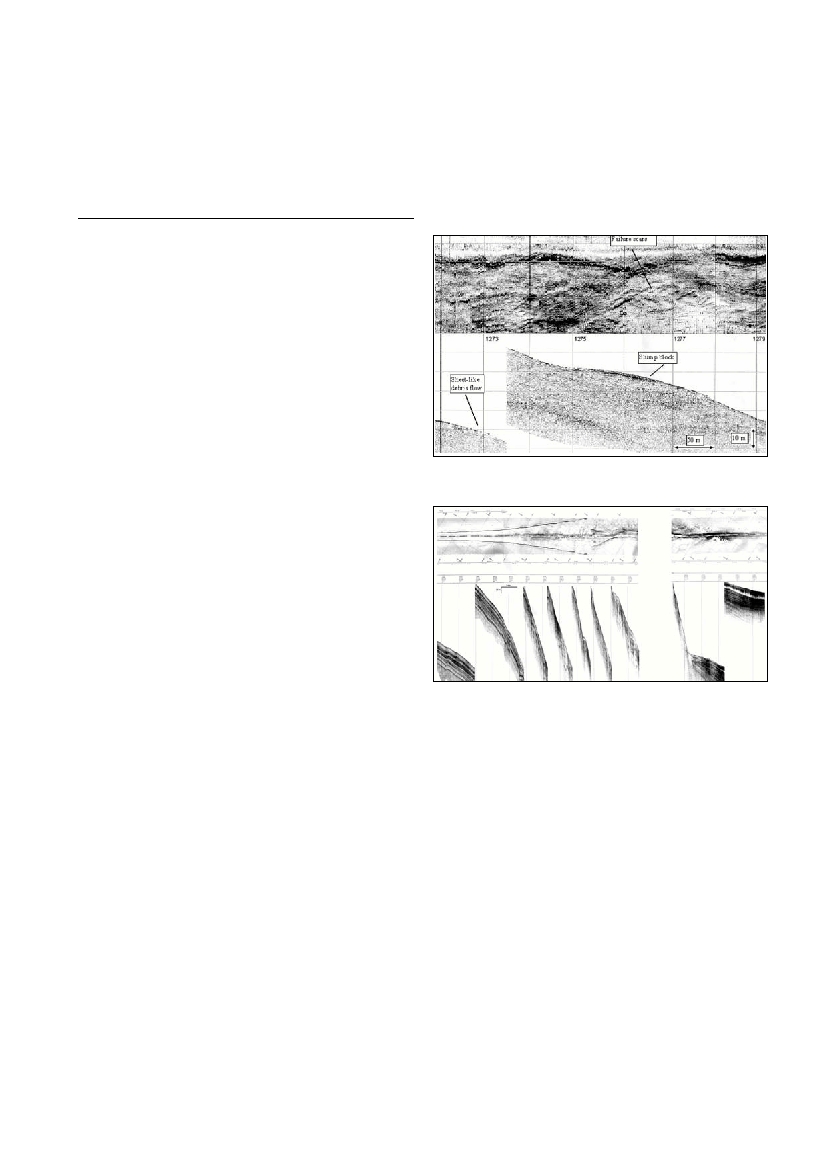

The sediments on the continental slope show slump and creep struc-

tures (Fig. 1). The seabed slumping and creep occurs mainly in areas

with slope gradients over 2°. During slumping, a mass of superficial

sediment becomes detached from a seabed slope along a slip plane and

moves downslope. Creep is the imperceptible but continuous move-

ment of sediment down a slope in response to gravity. It is a viscous

type of ?ow in which there is internal and permanent deformation. The

steep slope exhibits minor and major northward dipping listric faults

as a result of slump and creep features. The depth of the shallow gas

remains constant at 20 meters (4, 5).

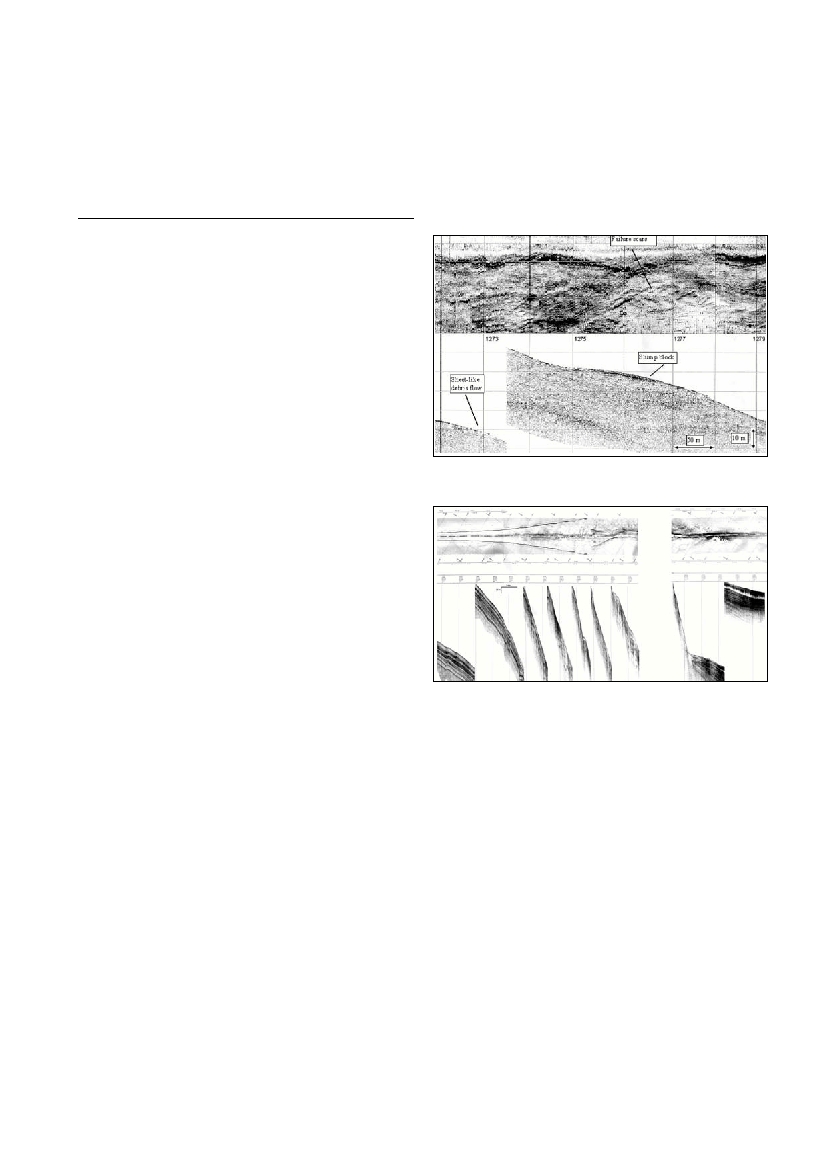

This has been clearly identified by the slide faults on the sonar and

especially the landslides on the subbottom profiler records. The chan-

nels can be identified clearly on the sonar mosaics, bathymetric charts

and subbottom profiler records, the channels are the best visible on the

cross-lines of subbottom profiles (Fig.2). The velocity and direction of

the sliding and ?owing down of the material is not constant along the

slope, but also in time duration. The sediment transportation direction

is controlled by the general direction of the slope and channel direc-

tion. These rivers have marked associated submarine canyon systems.

Turbidity current activity is responsible for much of the movement of

sediment into the canyons. Slumping or turbidity ?ows of sediment

from steep side walls of canyons is also thought to be a possible cause

of damming the main channel and delaying sediment transport.

References

1- Sengor A.M.C. and YilmazY., 1981. Tethyan Evolution of Turkey:A

PlateTectonic Approach, Tectonophysics, 75: 181-241.

2- Cifci G., Dondurur D. and Ergün M., 2000. Sonar and High

Resolution Seismic Studies in the Eastern Black Sea Basin, paper pre-

sented at the meeting of International Earth Sciences Colluquium on the

Aegean Region (IESCA-2000).

3-Woodside J.M., Ivanov M.K. and LimonovA.F., 1997. Neotectonics

and Fluid FlowThrough Sea Floor Sediments in the Eastern

Mediterranean and Black Seas. UNESCO reports in marine science,

Paris, No. 48.

4- Cifci G., KruglyakovV., Ergun M. and Pomomoryov I., 1998.

Acoustic Anomalies in Gas Saturated-Shallow Sediments in the Eastern

Black Sea, Proceedings of the 12th International Petroleum Congress and

Exhibition of Turkey, pp.400-411.

5- Ergun M. and Cifci G. 1999. Gas Saturated Shallow sediments in the

Eastern Black Sea and Geohazard effects, Proceedings of Offshore

Technology Conference, pp.621-630. Texas: USA.

HIGH RESOLUTION SEISMIC AND SONAR CHARACTERISTICS

OF THE EASTERN BLACK SEA TURKISH CONTINENTAL SLOPE

M. Ergun*, G. Cifci and D. Dondurur

Dokuz Eylul University, Engineering Faculty, Department of Geophysics, Tinaztepe Campus, Kaynaklar, Buca-Izmir,Turkey

mustafa.ergun@deu.edu.tr

Abstract

The Black Sea is one of the largest inland seas in the world. Off the shelf, the water depth quickly plunges to an average depth of 2 km

making it unusually deep for what would normally be termed a marginal sea. The slope failures and sediment instability are serious prob-

lems that can lead to the failure of offshore installations. Some marine geophysical surveys have been carried out in the Eastern Black Sea

basin and continental slope areas using state-of-art technology to produce sonar and high-resolution maps.

KeyWords: The Black Sea, Continental Slope, Sediment Transport.

Fig. 1. Detailed Chirp Side Scan Sonar and Subbottom Profiler record

example of a canyon wall. The subbottom record shows two slump

blocks and a sheet-like debris ?ow. Failure scars are visible as high

re?ectivity lineations on the side scan sonar record.

Fig. 2. Side scan sonar (top) and subbottom profiler (bottom) records

from Turkish Continental Slope.