Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 36,2001

32

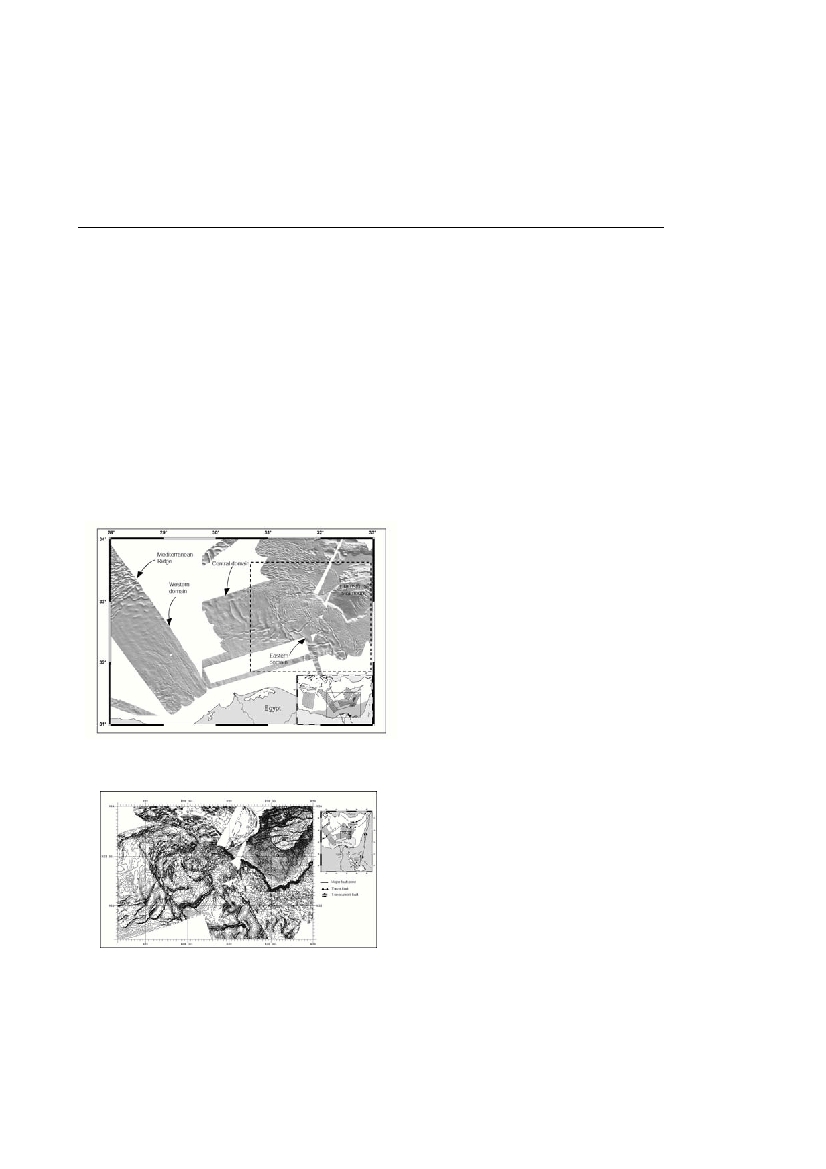

Deformation in the Mediterranean area involves both thick-skinned, crustal-

scale tectonics and thin-skinned, gravity-driven deformation of the Messinian

evaporites and their sediment overburden (5). This is particularly true in the Nile

deep-sea fan (Figure 1), recently surveyed during the Prismed II and Fanil sur-

veys (1998, 2000) using multibeam swath bathymetry and acoustic imagery,

seismic re?ection data and HR seismics. These surveys have evidenced differ-

ent structural features that have formed in response to either gravity-driven salt

tectonics due to loading of the Messinian evaporites by the Nile’s sediments (3)

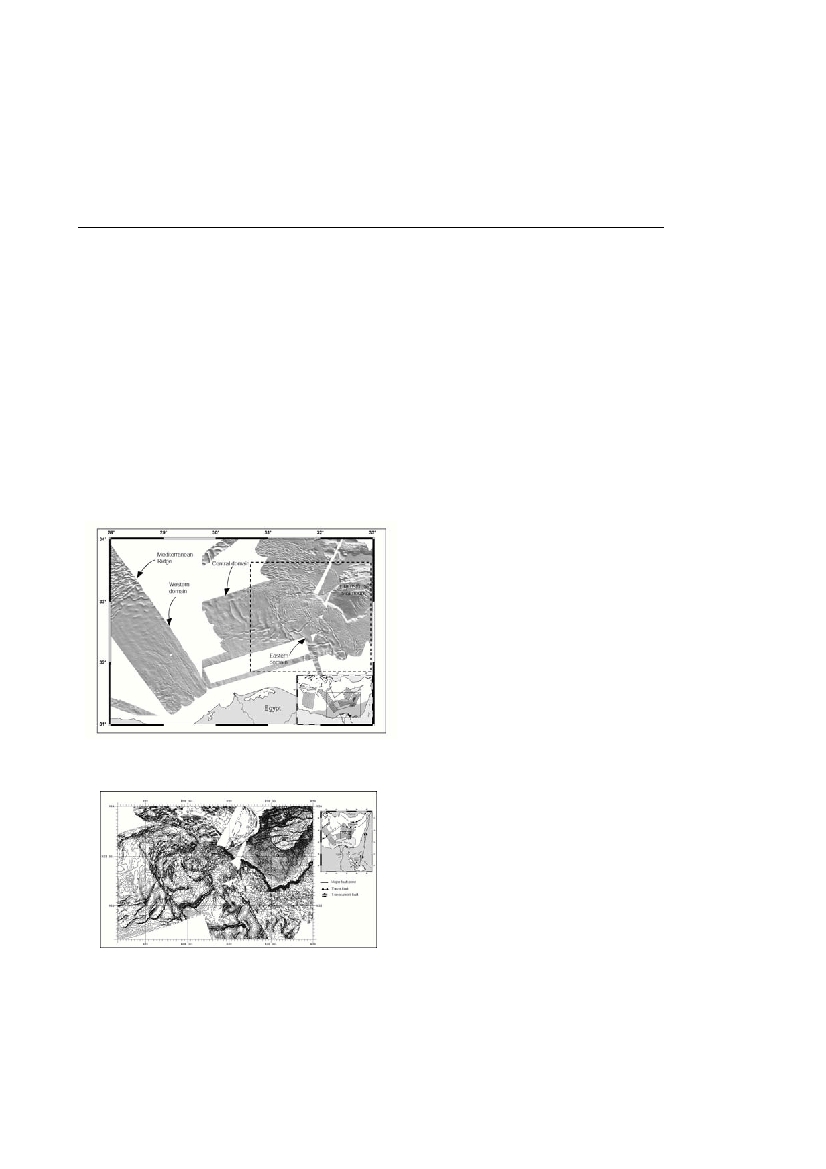

or to transtensional, deep-seated tectonics (1,2,4). In this area, it is particularly

difficult to distinguish structures that are truly related to large-scale tectonics

from those that are solely the result of salt tectonics and, therefore, cannot be

used as regional tectonic indicators (Figure 2). We consequently used experi-

mental modelling to test the structural patterns produced by gravity spreading

above salt where residual or active deep-seated relief is present.

3D spreading above active subsalt relief

In this experiment, we simulated radial spreading of a sediment lobe above

an active graben beneath the evaporites. Model results show that an active sub-

salt graben in?uences spreading of the lobe only after significant graben subsi-

dence has taken place, and that only a few structures formed with a trend paral-

lel to the graben orientation. In this experiment, ?ow pattern in distal area of the

greatly differed from what is observed in the Nile deep-sea fan.

To assess the contribution of a spreading lobe on the final deformation pat-

tern, we also run an experiment where syntectonic sediments aggraded only,

rather than prograded. In this model, some overburden structures formed paral-

lel to the graben direction, but did not link with the basement fa

u

l

t

s

.

Furthermore, the absence of polygonal depocentres or buckle folds makes this

model unable to explain the deformation pattern of the Nile deep-sea fan.

3D spreading above residual subsalt relief

We also studied the in?uence of a dormant subsalt graben, no longer active,

during progradation, and tested that set-up using lobes having various shapes.

Even during the early stages of deformation, a dormant subsalt graben in?u-

enced the spreading of the lobe by acting as an underlying corridor that chan-

nelled the movements of salt and overburden. The overburden located above the

dormant graben extended and subsided faster, which caused depocentres there

to be thicker. In addition, salt ?ow in the distal part of the models caused trains

of arcuate folds, a pattern exactly identical to that observed in the Nile deep-sea

fan. Experiments also indicate that formation of well-defined graben-parallel

faults or salt-ridges depends essentially on the planform geometry of the sedi-

mentary lobe: spreading of a circular lobe forms polygonal basins, having no

specific preferred fault orientation, rather than graben-parallel structures. By

contrast, when the lobe was elongate, numerous graben-parallel faults and

ridges formed throughout the model history.Wrench structures, grabens and

salt-ridges successively accommodated the overburden’s movements. These lin-

eaments can be reactivated in compression by spreading of other nearby lobes.

The following conclusions emerge from these experiments:

1. The main difference between radial spreading above dormant or active sub-

salt relief occurs during the early stages of overburden. Spreading is highly

channelled when the underlying subsalt graben is dormant, but is not when the

graben is active.

2. During the early stages of deformation, the evaporitic layer commonly decou-

pled the overburden from the subsalt basement. Basement faults did not propa-

gate through the salt layer.The connection between subsalt and suprasal struc-

tures took place only during the later stages of lobe spreading, during which

ponded basins became anchored onto the basement.

3. As long as the lobe had not subsided significantly, the basement’s in?uence

remained limited to causing variations in the rate of salt ?ow and overburden

movement, both of which essentially depend on the salt layer’s thickness.

Lateral variations in spreading rate induced apparent strike-slip movements

within the spreading overburden.

4. Spreading of an initially circular sediment lobe did not create a set of elon-

gate, graben-parallel features but mostly radially-oriented structures.

5. By contrast, spreading of an elongate lobe parallel to the subsalt graben

induced formation of different graben-parallel structures including wrench

zones, grabens or salt-ridges. These faulted structures widened during the late

stages of spreading, forming structural drains and pathways that can guide and

funnel the sediment transport. A nearby second spreading lobe can reactivate

some of these structures in compression.

Clearly, the structural pattern that developed in our experiments of prograda-

tion above dormant subsalt relief fits best the Nile deep-sea fan natural exam-

ple:For example, thin-skinned contraction, expressed by arcuate buckle folds in

the models, is extremely-well identified in the distal parts of the Nile deep-sea

fan. Furthermore, a huge NW-SE deformed belt in the Eastern Nile deep-sea fan

is associated, with transverse salt ridges, crestal grabens and polygonal

depocentres. A similar association of tectonic trends and structural styles is also

observed in models of lobes spreading above dormant basement relief.

References

1. Abdel Aal, A., A. El Barkooky, M. Gerrits, H. Meyer, M. Schwander, and H. Zaki,

2000(a), Habitat and exploration potential of the ultra-deepwater offshore Mediterranean:

EAGE conference on geology and petroleum geology, Malta, 1-4 october 2000.

2. Abdel Aal, A., A. El Barkooky, M. Gerrits, H. Meyer, M. Schwander, and H. Zaki,

2000(b),Tectonic evolution of the Eastern Mediterranean Basin and its significance for

hydrocarbon prospectivity in the ultradeepwater of the Nile Delta. The Leading Edge, v.

19, No. 10, p. 1086-1102

3. Gaullier,V.,Y. Mart, G. Bellaiche, J. Mascle, B. Vendeville,T. Zitter, and second leg

Prismed II scientific party, 2000, Salt tectonics in and around the Nile deep-sea fan :

insights from the PRISMED II cruise, in: B. C. Vendeville,Y. Mart, and J.L. Vigneresse,

Salt, Shales and Igneous Diapirs in and around Europe, Geological Society of London,

Special Publication, 174, p. 111-129.

4. Mascle J., J. Benkhelil, G. Bellaiche, T. Zitter, J. Woodside, L. Loncke and the Prismed

II scientific party (including V. Gaullier), 2000, Marine geological evidence for a

Levantine-Sinai plate, a missing piece of the Mediterranean puzzle: Geology,28, n°9,

p.779-782.

5.Vendeville, B. C., V. Gaullier L. Loncke and J. Mascle 2000, Gravity-driven tectonics in

salt provinces with implications for thin-skinned vs. thick-skinned deformation in the

Mediterranean: American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting, San Francisco, California

(USA), December 14-19, EOS, Transactions,AGU, 81 (48), p. F1224.

3-D EVOLUTION OF SEDIMENT LOBES ABOVE PRE-EXISTING DORMANT OR ACTIVE RELIEF.

IMPLICATIONS FOR THE NILE DEEP-SEA FAN, EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN

Loncke L.

1

*,Vendeville B. C.

2

, Gaullier V.

3

and Mascle J.

1

1

Géosciences-Azur, Observatoire Océanologique de Villefranche sur mer, France

2

, Bureau of Economic Geology,The University of Texas, Austin, Texas, USA

3

Faculté des Sciences, Université de Perpignan, France

Abstract

We conducted a series of physical experiments to better understand the complex structural pattern in the Nile deep-sea fan, where thin-

skinned tectonics due to sediment loading of Messinian evaporites and deep-seated tectonics interact. Experiments tested the in?uence of

active or dormant subsalt relief during progradation of sediment lobes. Results from models where the subsalt graben was dormant show

the best fit with the structural pattern observed in the Nile-deep-sea fan.

Key-words: experimental modelling, Nile deep-sea fan, thin-skinned tectonics, thick-skinned tectonics, salt tectonics.

Figure1: Shaded bathymetry of the Nile deep-sea fan, acquired during

the Prismed II cruise. This fan has been divided in 3 main morphostruc-

tural provinces: a Western, a Central and an Eastern province. The dot-

ted frame indicate the area that has been compared with physical

Figure 2: Eastern domain of the Nile deep-sea fan showing a complex

structural pattern corresponding to both thin-skinned tectonics due to

sediment loading of Messinian evaporites and deep-seated tectonics.

This morphostructural domain was compared to experiments that tes-

ted the in?uence of active or dormant subsalt relief during progradation