Rapp. Comm. int. Mer Médit., 36,2001

43

Introduction

The Gulf of Corinth is the most active extensional feature in Europe

with a maximum extension rate in N-S direction of 7-16 mm/yr (1,2).

With a general WNW-ESE elongate shape, the Gulf of Corinth sepa-

rates the clockwise rotating Peloponese to the south from the relative-

ly stable Central Greece to the North. The up to 900m deep basin

crosscuts the NNW-SSE trending alpine structure of the Hellenides,

limiting the occurrence of Parnass unit to the North and the external

metamorphic belt to the South, and disrupting the nape structure of

Pindos unit.

Faulting and evolution

A grid of densely spaced (every 1 mile) N-S single-channel Air Gun

p

r

o

files was performed in the entire Gulf of Corinth (from Rion-

Antirrion to the Gulf of A

l

kyonides) and provided maximum penetration

of 1sec twtt within the basin’s sediments and relatively high-resolution.

The present Gulf-of-Corinth basin is controlled by two main

marginal fault zones, which run along the foot of the southern and

northern submarine slopes. Each fault zone consists of a number of E-

W trending, en echelon arranged, fault-segments. Both slopes are

steep and display extensive failure phenomena. In contrast to the pro-

posed asymmetric character of the basin (3), favoured by most work-

ers up to now, the structure of the present-day Gulf of Corinth appears

much more complicate.

Starting from the East, the Psatha fault and its westward prolonga-

tion along the foot of the southern slope controls the evolution of the

Gulf of Alkyonides basin. Both the sea-bed and the sediments dip

southwards, while the lowermost horizons of the 400m thick basin

infill are correlated with the Pleistocene conglomerates of the inactive

Megara basin, presently exposed at 300m altitude (4).

Moving to the West, the 800-900 m deep basin of the central Gulf

of Corinth displays rather symmetric character.The basin infill con-

sists of continuous turbidite sedimentation and is intersected by nar-

row zones of transpressional deformation, bordered by E-W trending,

intra-basinal, high-angle faults. Massive sliding structures occur all

along the steep southern and northern slopes. The Perachora peninsu-

la, which is bordered by the NW-facing Perachora fault and the S-ward

dipping Loutraki fault, separates the central basin of the Gulf of

Corinth from the N-ward tilted Lechaion Gulf basin.

Further to the West the active Gulf of Corinth basin becomes sig-

nificantly narrower and shallower, while the maximum sediment accu-

mulation thickness decreases gradually from >800m in the eastern part

to <400m offAigio. Between Galaxidi and Aigio the basin infill con-

sists mainly of chaotic slide masses, while continuous sedimentary

re?ectors are poorly observed. The lower horizons of the sedimentary

sequence are strongly deformed and dip gently to the N, indicating a

possible N-ward tilting of this part of the basin.

The westernmost part of the basin is occupied by the prodelta and

distal deposits of Erineos and Mornos rivers. Frequent slope failure

phenomena occur along both the southern and northern 200m high

escarpments, which border the narrow basin.

The southern margin of the present Gulf undergoes continuous

uplift, indicated by the presence of elevated marine terraces (5,1), and

the uplifted Pleistocene delta deposits in Northern Peloponese (6).

Opposite to that, the northern margin of the Gulf undergoes continu-

ous subsidence during the last 250 ka, as shown by the presence of

several low-sea-level-stand prograding sequences on the outer self and

upper slope off Eratini (7).

Discussion

The present Gulf of Corinth represents the last stage of an older

structure, which initiated in Upper Miocene – Lower Pliocene. The

opening of the basin either started earlier in the eastern part or pro-

graded faster in the east than in the west. This assumption may explain

the widening, deepening and higher sediment accumulation of the

basin toward East and coincides with the clockwise rotation of

Peloponese. During the evolution of the basin the southern active mar-

gin was migrating northwards and the northern one remained more or

less stable inducing northward shifting of the active basin. The rather

complicate structure of the present day Gulf of Corinth basin is not

easily explained by the presence of a low-angle N-dipping normal

fault / seismogenic layer below the Gulf, which is proposed by many

authors.

References

(1) Armijo R., Meyer B., King G., Rigo A. and Papanastassiou D., 1996.

Quarternary evolution of the Corinth rift and its implications for the late ceno-

zoic evolution of the Aegean. Geoph. J. Int.,

126/1: 11-53.

(2) Davies R.R., England P.C., Parson B.E.,

Billiris H., Paradissis D. and Veis G., 1997.

Geodetic strain of Greece in the interval

1892-1992.J. Geophys. Res., 102: 24,571-

24, 588.

(3) Brooks N. and Ferentinos G., 1984.

Tectonics and sedimentology in the Gulf of

Corinth and Zakynthos and Kefallinia

chanels, western Greece. Tectonoph.,101:

25-54.

(4) Sakellariou, D., Lykousis V. and Papani-

kolaou D., 1998. Neotectonic and evolution

of the Gulf of Alkyonides, Central Greece.

Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece, 32/1: 241-250.

(5) Keraudren B. and Sorel D., 1987. The ter-

races of Corinth (Greece) - A detailled record

of eustatic sea-level variations during the last

500,000 years. M

a

r. Geol., 77: 99-107.

(6) Ori G.G., 1989. Geologic history of the

extensional basin of the Gulf of Corinth

(?Miocene- Pleistocene). G

e

o

l

og

y, 17: 918-921.

(7) Lykousis V., Sakellariou D. and Papani-

kolaou D., 1998. Sequence stratigraphy in

the N. margin of the Gulf of Corinth:

Implications to Upper Quaternary basin evo-

lution.Bull. Geol. Soc. Greece, 32/2: 157-

164.

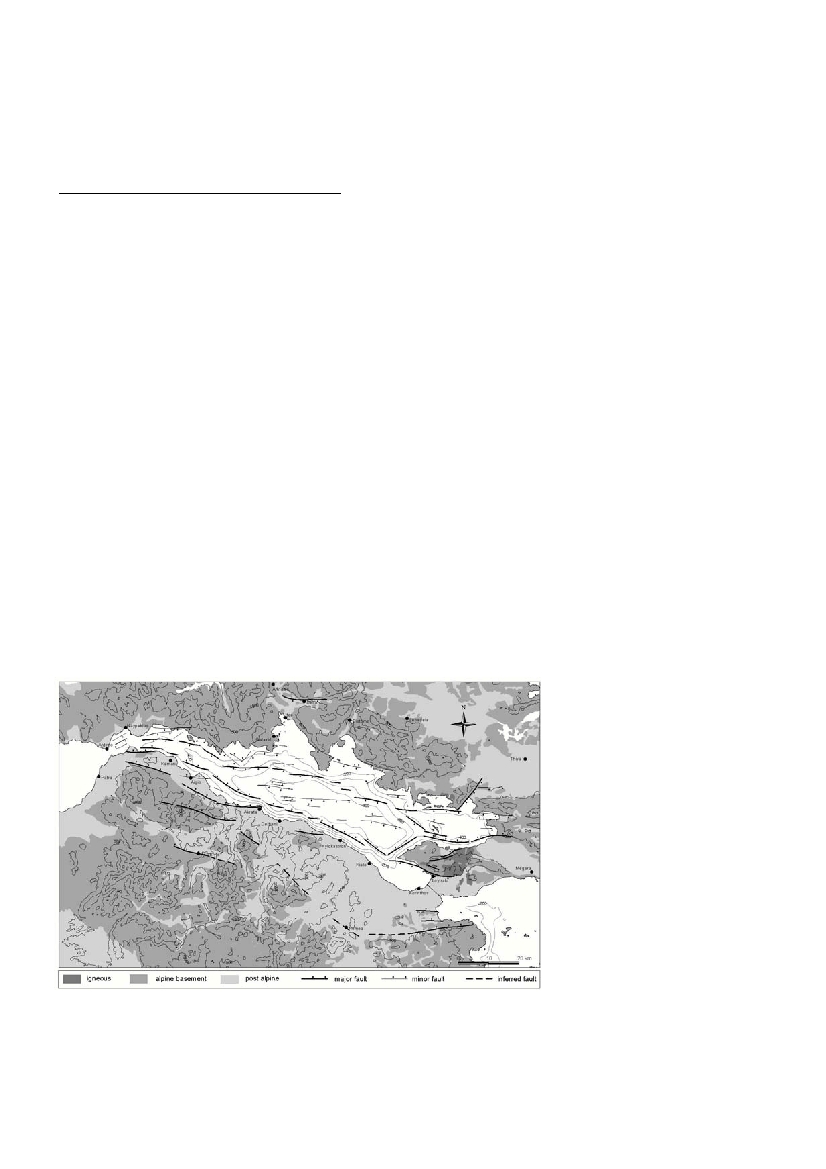

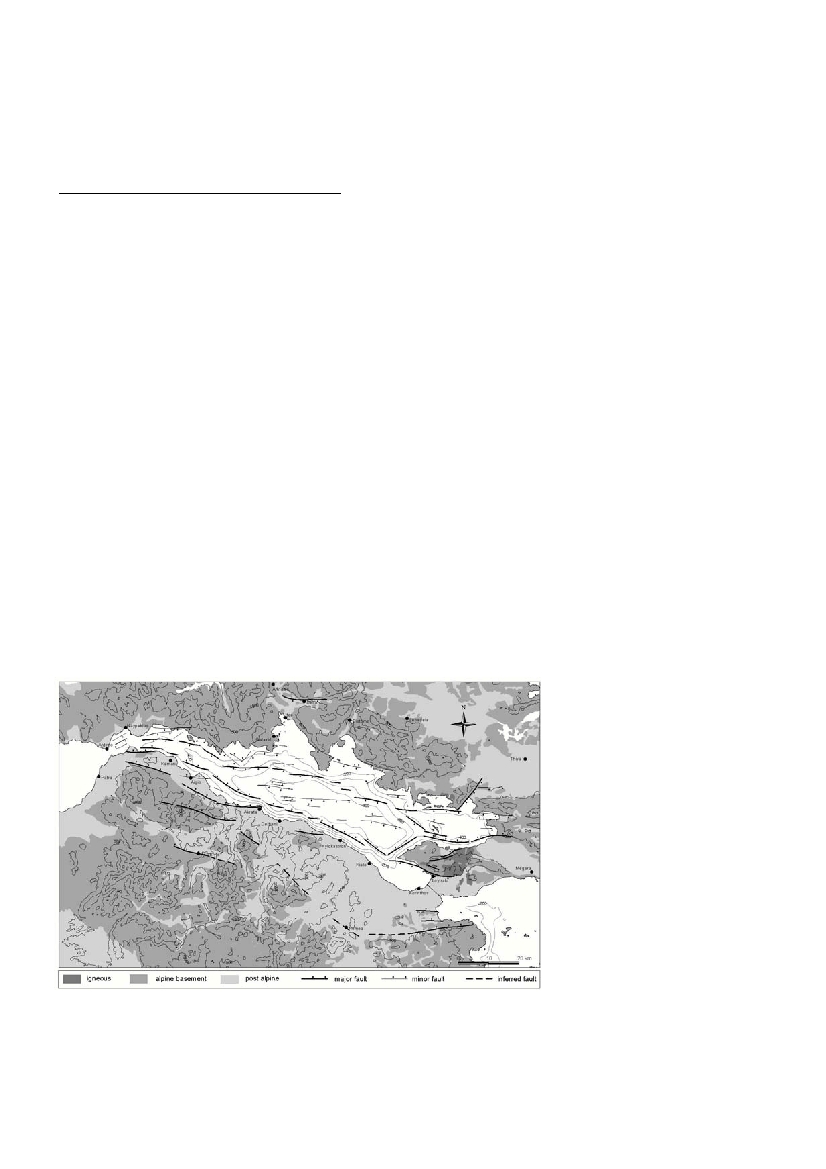

ACTIVE FAULTING IN THE GULF OF CORINTH, GREECE

D. Sakellariou*, V. Lykousis and D. Papanikolaou

National Centre for Marine Research, Athens, Greece - sakell@?.ncmr.gr

Abstract

High resolution seismic profiling in the Gulf of Corinth indicates more complicate structure than thought up to now.Two equivalently

active fault zones, each one composed of several en echelon arranged fault-segments, border the basin north- and southwards. The basin

becomes narrower and shallower toward west, while significant transpressional deformation occurs along narrow zones.

Key words : Tectonics, Stratigraphy, Seismics, Sea Level

Fig. 1: Active faulting in the Gulf of Corinth basin.