Deep-diving record in the Ligurian Sea Deep-diving record in the Ligurian Sea

October 2006 , CIESM News

|

| The average foraging dives of beaked whales are deeper and longer than reported for any other air-breathing species. They prey by echolocation in deep water and manage to access food sources at about 1900 m depth. Not even elephant seals or sperm whales, marine mammals known for their remarkable abilities for breath-hold diving, are capable to reach such depths.

The family of beaked whales include some of the world’s most cryptic and difficult to study mammals. Only little is known about the diving behaviour and physiology of Cuvier’s (Ziphius cavirostris) and Blainville’s (Mesoplodon densirostris) beaked whales. An international team of scientists recently studied* these species in Italian and Spanish waters, using non-invasive sound and orientation recording tags.

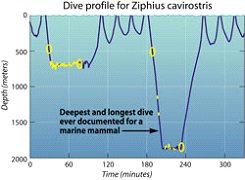

Tags were attached to seven Cuvier’s beaked whales in the Ligurian Sea and three Blainville’s beaked whales were tagged in the Canary Islands. The analysis of the collected data showed that the Cuvier’s beaked whales reached down to nearly 1900 m depth with a maximum duration of 85 minutes, while Blainville’s beaked whales dove to a maximum depth of 1250 m and 57 minutes in duration. The dives near 1900 m constitute the deepest confirmed dives reported from any air-breathing animal.

|

|

|

| |

The scientists Peter Tyack (left) and Mark Johnson with a D-tag in the foreground. Attached to the whale by suction cups, these devices hold a variety of sensors to record sounds and movements. For this study, they were programmed to release automatically from the animal at the end of the recording time (after about 8-12h) and to come back to the sea surface where they were tracked and recovered. The sensor data were then off-loaded to a computer for analysis.

(Photo by Tom Kleindinst, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

|

|

|

A Cuvier's beaked whale in the Ligurian Sea. For this area, the whale watch company BluWest had excellent sighting data for this species which allowed the scientists to locate and tag them. Sized 5.5-7 m and with 2-3 tons, the Cuvier's beaked whales feed on deep-sea fish and squid.

(Photo courtesy of Natacha Aguilar de Soto, University of La Laguna, Spain) |

|

Even more important than the maximum is the average of the deep dives. Regular echolocation clicks and buzzes as well as echoes from what appears to be prey were recorded on the tags, suggesting that the whales were hunting for food on their deep dives. For the Cuvier’s beaked whales, the average foraging dive went to a depth of 1070 m with a duration of about an hour. These dive data also represent the deepest average dive as well as the longest one reported from any air-breathing animal.

For comparison: the much better studied sperm whale typically dives for 45 minutes to depths of 600-1000 m.

|

|

This graph shows the depth and duration of a Cuvier's beaked whale, Ziphius cavirostris.

(Courtesy of Peter Tyack et al.)

|

After long and deep dives to find food, the two beaked whale species make a series of shallower dives, providing no indications of foraging. The scientists interpret that beaked whales return to the surface with an oxygen dept accrued in the deep foraging dives and need to recover before the next deep-sea hunting.

To understand how the deep-diving Cuvier’s and the Blainville’s beaked whales operate is also of particular interest, because both species have been reported to mass strand during naval sonar exercises. Autopsies of the carcasses showed symptoms of decompression sickness. Using current models of breath-hold diving, the authors infer that the natural diving behaviour of the whales rules out the hypothesis of problems of acute nitrogen supersaturation and embolism. Presuming the assumptions of the models also correct for beaked whales, their study rather suggests that a physiological risk would stem from an abnormal behavioural response to sonar.

'One of the most important things about this work is that it has given us a new view on how marine mammals forage using biosonar'** adds Peter Tyack, senior scientist in marine biology 'and that the clicks made by beaked whales open a new potential to monitor for their presence by listening for their clicks'.

|

* P. L. Tyack, M. Johnson, N. Aguilar de Soto, A. Sturlese and P. T. Madsen, 2006. Extreme diving of beaked whales. The Journal of Experimental Biology, 209: 4238-4253.

** see P. T. Madsen, M. Johnson, N. Aguilar de Soto, W. M. X. Zimmer and P. L. Tyack, 2005. Biosonar performance of foraging beaked whale (Mesoplodon densirostris). The Journal of Experimental Biology, 208: 181-194.

|

CIESM information on marine mammals in the Mediterranean Sea is available here:

- CIESM Monograph n° 25 - Investigating the roles of cetaceans in marine ecosystems.

- CIESM Task Force on Marine Mammals: see report.

CIESM-Ifremer morpho-bathymetric maps of various sectors of the Mediterranean Sea, including the Ligurian Sea, are available here.

|

|